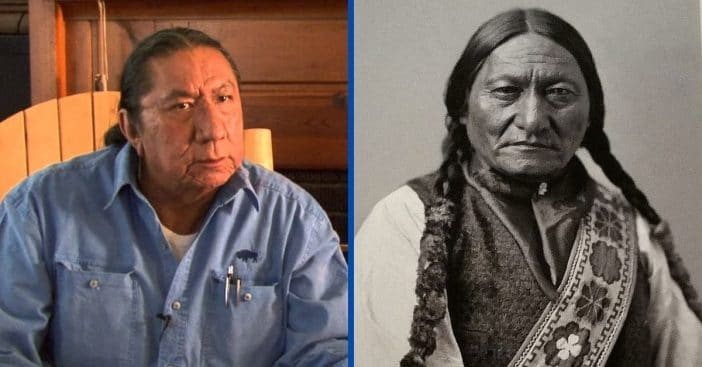

South Dakota resident Ernie LaPointe has long asserted his blood relation to Lakota Sioux chief Sitting Bull. This week, scientists shared peer-reviewed results in the journal Science Advances saying that not only did DNA testing at last confirm LaPointe’s claims, but the technique itself is revolutionary and this breakthrough is the first of its kind.

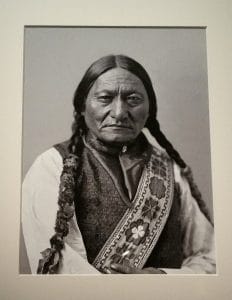

Testing was performed on a hair sample from Sitting Bull himself, who died in 1890. The results were compared to the DNA of LaPointe, who is today 73, and indicate he is the late Native American leader’s great-grandson. He also founded the Sitting Bull Family Foundation (SBFF), a nonprofit dedicated to providing an accurate oral history of Sitting Bull and the Lakota people.

A breakthrough in DNA research and science confirmed Ernie LaPointe as the great-grandson of Sitting Bull

Scientists confirm man is Sitting Bull's living descendant

+ They analyzed DNA from legendary Native American chief's hair

+ New technique paves way for testing of long-dead historical figures

READ MORE: https://t.co/uYZV5A6AkK pic.twitter.com/CLx4N7ItDw

— Daily Mail US (@DailyMail) October 28, 2021

The SBFF website traced LaPointe’s relation to Sitting Bull along with his being a descendant from a long line of chiefs on both sides of his family. In their article published to Science Advances, researchers state that this is the first time DNA from a deceased individual – especially one separated so much temporally – has been used to confirm a biological connection to a living individual. Their methods use ancient DNA to further test against the modern individual’s DNA. This historic revelation comes from the University of Copenhagen’s Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Centre, developed by Director Eske Willerslev.

RELATED: Boy That Was Kidnapped Back In 1964 Found Through Ancestry Records

According to Willerslev, he learned of LaPointe’s desire to formally prove a blood relation. Willerslev offered help, and LaPointe “asked me to extract DNA from [the hair] and compare it to his DNA to establish relationship.” Once they had their task, they needed to think of how to perform it. “I got very little hair and there was very limited DNA in it. It took us a long time developing a method that, based on limited ancient DNA, can by compared to that of living people across multiple generations,” Willerslev shared. For Willerslev, this was also an exciting chance to indulge in his fascination with Sitting Bull, who he considers “the perfect leader — brave and clever, but also kind.”

The hair sample used for this test was taken by H. Deeble, a surgeon at Fort Yates, who extracted a lock of hair before Sitting Bull was buried, in addition to the chief’s cloth leggings as souvenirs. They ended up loaned to the Smithsonian who gave them both back to LaPointe and his sisters. During its stay at the Smithsonian, it was reportedly stored at room temperature, leaving it degraded and further limiting what scientists could extract from it. “There was very little DNA in the hair — way too little for established methods of DNA analysis,” Willerslev confirmed. “So we had to develop a new method.” That new method took 14 years to develop, and involved using what little bit of DNA they could get from Sitting Bull and comparing it with LaPointe, and other Lakota Sioux to prove a family connection.

They also had to rely on autosomal DNA, which is the inherited genetic material children get from both parents. This is in contrast to mitochondrial DNA, which mothers pass on to their female and male children, and Y-chromosomal DNA, which fathers only pass on to their sons. LaPointe’s connection came from his mother’s side, so she would have no Y-chromosomal DNA from Sitting Bull to pass on.

Continuing to preserve history at a personal and macro scale

This research represents major breakthroughs for the past, present, and future of science, genealogy, history, and genetics. It is, to the authors’ knowledge, the first peer-reviewed published instance of confirming ancestral relations between the living and the dead all while “such limited amounts of ancient DNA across such distant relatives.” As the paper’s abstract concludes, this power can end up “broadening genealogical research, even when only minor amounts of ancient genetic material are accessible.”

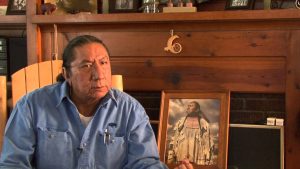

For Ernie LaPointe, it means strengthening his mission to immortalize and treasure the legacy of Sitting Bull and the Lakota people. Sitting Bull, known also as Tatanka Iyotake, was born in 1831 and became a major leader in Native American resistance against encroaching colonialism and conflict against his peers. He is credited with united several Sioux tribes in this common cause and led them to victory in the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn against General Custer. He gained much influence thanks to his prophetic vision of victory, carrying out this vision, refusing to surrender against the government’s retaliatory blows, and as a prominent performer in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. His influence grew so great, it was feared he could bolster the Ghost Dance movement, and it was during the subsequent arrest that Sitting Bull was ultimately killed.

LaPointe knows this is not the end of the road for compiling a comprehensive and ongoing history of Sitting Bull and his family. “People have been questioning our relationship to our ancestor as long as I can remember,” he said. “These people are just a pain in the place you sit — and will probably doubt these findings, also.” However, it was an important step in many regards. For one thing, it will help LaPointe in his mission to have the authority to move Sitting Bull’s remains from their current burial site of Mobridge, South Dakota to somewhere with more cultural significance.