UPDATED 8/8/2023

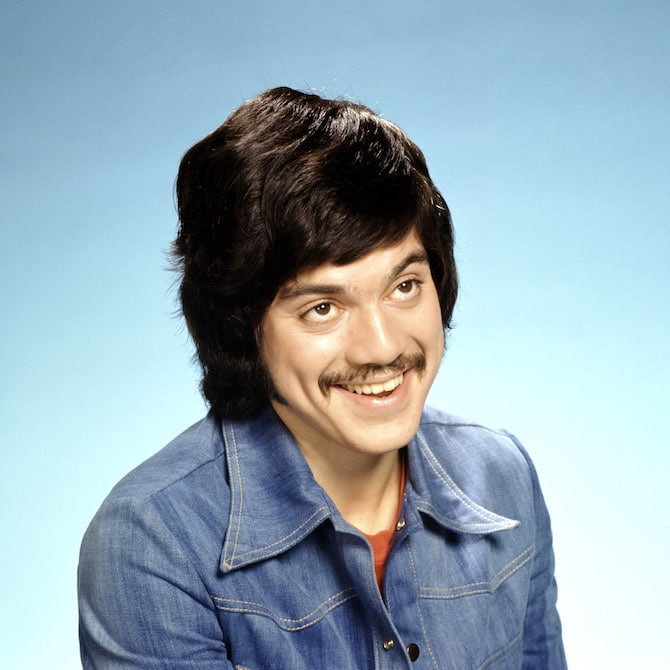

If you were to seek out the perfect example of the adage that the candle that burns twice as bright, burns half as long, you wouldn’t have to look any further than Freddie Prinze, star of the phenomenally successful 1970s sitcom, Chico and the Man.

Freddie (father of actor Freddie Prinze, Jr.) was someone who seemed to have come out of nowhere, quickly had the Hollywood world at his feet and yet was haunted by such personal demons that he elected to end his life at the age of 22. This was not the way that anyone could have imagined things ending.

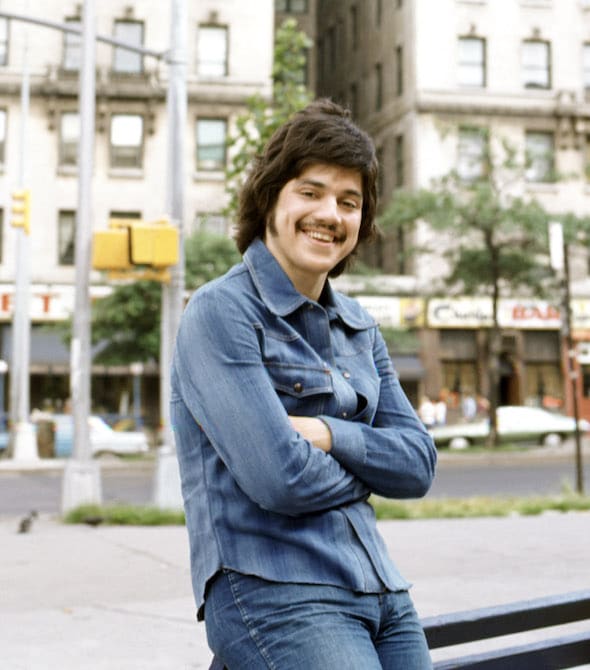

He was born Frederick Karl Pruetzel (later changing his name to Frederick James Prinze) on June 22, 1954, in New York City to Puerto Rican and German parents. He was raised in the mixed neighborhood of Washington Heights, which wasn’t easy. Of his background, he reflected to the media, “I was too fat to play ball and my mouth was quicker than my fists. I was big, but the kids didn’t know I couldn’t fight. Like all other comics, I wanted recognition. I felt I had to be funny to get acceptance. If you were going to survive on the streets, you had to be either tough or funny. I was funny. I’d wander into my parents’ room in the middle of the night with the old Ed Sullivan routine, ‘Well, here it is the morning and we’ve got a really big shew for you.’”

It’s hard to say how appreciated those early morning sessions were, but no one can argue the road it ultimately led Freddie on.

Rising Comic

In detailing his background, Freddie shared with the Austin American Standard in 1974, “My mother, the Puerto Rican, wanted me to be into music, so I learned to play the guitar by ear. Then she stuck me in ballet school, which of course I hated, but wound up taking it for four years. And when I went to the New York High School for the Performing Arts, I took drama. The last few years I started doing standup comedy in nightclubs. Now I am back into acting. Maybe soon I’ll be doing ballet again. Whatever comes, I am ready.”

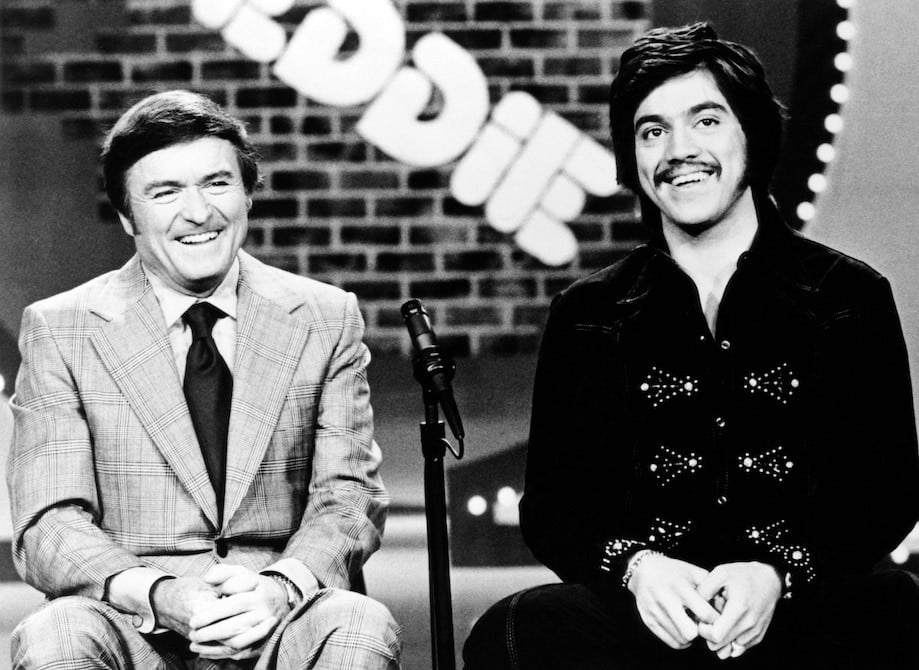

Honing his craft actually came from studying himself. He related to The Shreveport Journal, “I would go on stage with a tape recorder and start improvising. You get up there on stage with total abandon. It’s the only way I know how to create material. Afterwards, I play it back and polish it up. When I went on with Johnny Carson for the first time, I had seven ‘killer’ shots in my routine. Usually, you only have two, but I wanted to really hit it my first time out.”

That same year, the Intelligencer Journal of Lancaster, Pennsylvania reported, “At 19 he’s a year and a half out of the ghetto and bright beyond his years. He’s been on the nightclub circuit for the past year pointing ethnic barbs at audiences across the country. It was that humor that took him to the Jack Parr Show, to The Merv Griffin Show, and ultimately to five Tonight Show appearances.” Later to grow to 20.

Of the latter point, Wikipedia notes, “Prinze was the first young comedian to be asked to have a sit-down chat with Caron on his first appearance. Prinze appeared on and guest-hosted The Tonight Show on several other occasions.”

Chico and the Man

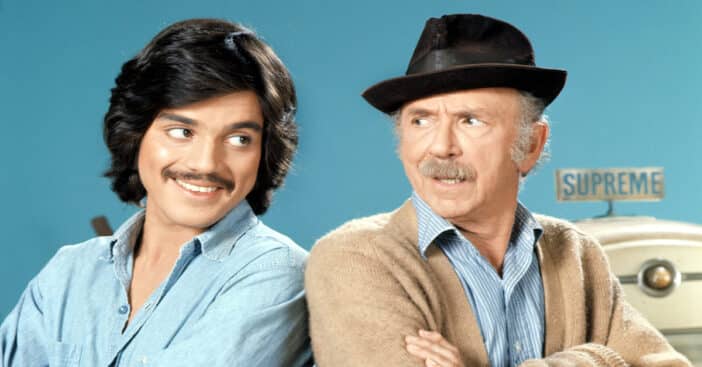

It was actually his appearances on The Tonight Show that brought him to the attention of the producers of Chico and the Man. That show, which ran on NBC from 1974 to 1978, stars Jack Albertson (Uncle Joe from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory and The Poseidon Adventure) as Ed Brown, the grumpy owner of a run-down garage in an East Los Angeles barrio, and Freddie as Chico Rodriguez, a positive-thinking young Mexican who arrives looking for a job. Described series creator James Komack (The Courtship of Eddie’s Father, Welcome Back, Kotter) at the time, “This is a comedy about an old man and a hustling kid who won’t let him give up on life. Warmth between the two is going to sell this more than the comedy.”

He was right and the impact was immediate: Chico and the Man was a ratings blockbuster and Freddie instantly found himself propelled into superstardom — which wasn’t an easy thing for him to grapple with.

“I’m still the same kid I was when I first came to Hollywood last year,” he emphasized to The Gazette of Cedar Rapids, Iowa in 1975. “I still live in the same one-bedroom apartment I rented a year ago and I still have no money. Not only that, I still get dumbstruck when I pass someone like Johnny Carson in the corridor and he says, ‘Hi.’ I think to myself, ‘Hey, that’s a big time star and he said hello to me.’ It’s like my producer, Jimmy Komack, told me when we started. The acting thing is no sweat, it’s dynamite, you got no problems there, Freddie. But it’ll be the little hassles, the unexpected things that will get you — the ones that drive all entertainers crazy. Things like the fan mail and the presents from fans and trying to juggle appointments with agents and managers and all.”

The pressures definitely mounted. He recorded several comedy albums and made television appearances on The Hollywood Squares, Tony Orlando and Dawn and Van Dyke and Company, as well as starring in the 1976 TV movie The Million Dollar Rip-Off. He also appeared at evangelist Oral Roberts’ Easter special for a very personal reason.

“I owe him,” explained Freddie. “That man has done a lot for me. When I was little and had asthma so bad, it was through his inspiration that I got well. Mom has been a big Oral Roberts follower for years, and she turned me on to him. He’s the reason I’m where I’m at today. I’m not a regular churchgoer, but I still consider myself a very religious person and I’m going on that special to give testimony, man. Just to say I have the faith and it’s worked for me. And that God smiles on you when you believe in Him.”

On top of everything else, he found himself headlining at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas and earning $25,000 a week. “I wish the offer had not come along for a year or two,” he reflected, “because Vegas is a place that you really should work your way up to.”

And yet through it all, he did his best to hold on to his modesty and not succumb to the trappings of stardom. As he pointed out to The Orlando Sentinel in 1977, “I turned down the chance to record a singing album, because I’m no singer. I’m not going to try to become another Frank Sinatra when that’s not my thing. I’m not going to let them mold me into something I’m not for the sake of the quick buck. I’ve told them I won’t capitalize on my Chico character just to grab a quick buck. I’ve told them I’m interested in a long-range career for Freddie Prinze and won’t do anything to jeopardize it. And I’ve told them I won’t do any publicity that smacks of gimmicks or stunts. I’m happy to meet with the press and be honest and real. And if I’m liked for what I am, that’s just fine.

“I have tunnel vision about my career,” he added. “I don’t want to clutter my mind, or my energies, with too many side endeavors. I’ll probably wait until Chico is through before I start concentrating on movies.”

Why did Freddie Prinze Take His Own Life?

Professionally, Freddie seemed to have it all together, but things were very different in his personal life. On October 13, 1975, he married Katherine Elaine Cochran, who gave birth to their son, eventual actor Freddie Prinze, Jr., on March 8, 1976. But there were tensions in the marriage, no doubt intensified by Freddie’s growing addiction to Quaaludes, which resulted in his being arrested for driving under their influence in 1976. A few weeks later, Katherine filed for divorce, filling Freddie with dread she’d take their son out of state. On top of all of this, he suffered from severe depression issues that were taking their toll.

It turns out that Freddie had a tendency to play Russian roulette to scare his friends and give himself amusement. On the night of January 28, 1977, during a visit by his manager, Marvin Snyder, he shockingly pulled out the gun and shot himself in the head. He would be placed on life support at UCLA Medical Center, though he was removed from it on January 29 at 1PM, when he was declared dead at the age of 22.

“He was in turmoil,” Tony Orlando would state. “He was suffering such pain, and yet his audience never knew. Two years ago he told me, ‘I’m only here temporarily. I have a feeling I should go home and there ain’t no ghettos where I come from.'” Naturally, the “home” he was talking about was heaven.

Added Budd Friedman, who ran the Improvisation showcase in Hollywood, “The difference between Freddie’s professional conduct and the way he handled his personal life were immeasurable.”

“He said, even in the very beginning of Chico and the Man,” Jack Albertson explained, “that he expected not to get past the age of 30.”

The people that had so quickly fallen in love with the comic brilliance of Freddie Prinze, were left stunned and reeling by news of his death, especially by the fact that the image he presented to them was so diametrically opposed to what he hid.

“On the series,” he said in 1975, “I keep saying, ‘Is not my job,’ but I do have a job — and that’s to make people laugh. That’s all I want to do. And, man, I’m lucky I’m getting a chance to do it.”