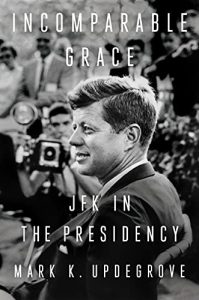

It’s common practice for public figures to don an acceptable or likable persona in front of potential supporters. At the very least, they have something about them that is magnetic, from what is known and what is left a mystery. In life, John F. Kennedy was a famous mystery of contradictions, and the book Incomparable Grace: JFK in the Presidency explores such paradoxes that were amassed before his death.

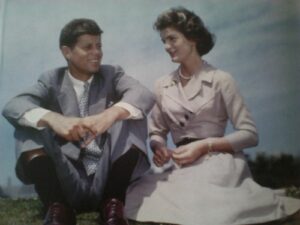

In particular, author Mark K. Updegrove explores the challenges that arose by circumstances, the trials allegedly of his own making, and the way tragedy offered some healing for him and Jackie Kennedy – even if just a bit – before defining a lot of his legacy and that of his family. Just how much cheating went on and how did an image of mystique combat this incriminating vice?

Infamy and mysticism

Updegrove, who has experience as a presidential historian, explores some of the carnal scandals that marked the latter years of JFK’s life. The late president’s aura fed into the reputation he developed and the rumors that surrounded him. For instance, Updegrove consulted actress Angie Dickinson as a confidante of JFK for the book. He asked about the rumors of an affair between the two, to which Dickinson said, “We had a lot of fun thinking about it.”

RELATED: Almost 60 Years After JFK’s Presidency: See What The Kennedy Grandkids Are Up To Now

Incomparable Grace attributes JFK’s desire for physical intimacy to cortisone shots he received on a daily basis to his back. Those desires, Updegrove claims, were “fed all too readily by friends and acolytes eager to indulge him by finding willing partners: socialites, movie stars, White House secretaries and interns, and high‐end prostitutes—anyone would do.” A popular rumor suggests that included Marilyn Monroe whose own death, theorists posit, was actually deliberately caused because she had intimate details of the Kennedy family. But once his reputation gained such momentum for reportedly indulging in affairs, how did it change course?

Incomparable grace when needed

Updegrove puts this rumored philandering into the context of JFK’s family life. When, in 1956, wife Jackie had given birth to daughter Arabella, who was stillborn, JFK had actually been off the coast of Italy, in Capri for a holiday cruise. At that time, he was a Senator, and his Florida colleague George Smathers warned him that failure to return home to comfort his wife and bury their daughter would put an end to his career in politics.

JFK heeded this advice and was even more readily on standby when Jackie gave birth to Patrick. Here, Updegrove suggests, “as [he] rushed to New England, his mixed record as a husband and father surely must have weighed on his mind.” He seemed on track to becoming a family man again. Sadly, Kennedy would end up holding his son’s hand as the baby passed away early the next morning. That’s when it is written that Kennedy retreated for some privacy and “he sobbed over the loss.” Tragedy had opened the gates to make way for definitive humanity and compassion and when JFK spoke with Jackie after this latest loss, she admitted, “There’s one thing I couldn’t stand. If I lost you.” So, Jackie had a man she could stand by and stand vigil over after his death, though now a characterization of Kennedy is like a tangle of conflicting traits, all coexisting in one source, as Incomparable Grace reminds readers of the power behind housing such a mythical aura.