“I knew I had that instability and dysfunction in me, from the way I grew up,” says McGraw. “And when I met Faith, I knew I needed her in my life — to keep me stable, solid and on track.”

Hill’s parents, Edna (a bank teller) and Ted (a factory worker), never hid the fact that they had adopted her, though they claimed her mother put her up for adoption because she’d had an affair with a married man, which wasn’t true.

View this post on Instagram

“I used to think there was some kind of conspiracy, that I must be the daughter of one of my aunts. And of course I used to dream I was Elvis’ daughter,” Hill says with a laugh. “I have a great family: salt of the earth, hardworking. But I’m a gypsy at heart. I had a spirit that was completely outside what my family was. I didn’t know anyone I was related to, biologically, which gives you a sense of not knowing who you are.”

In her early 20s, after Hill moved from Star, Miss., to Nashville, she began to look for her birth family. She located her biological mother, a professional painter, and learned she had a full brother too. Knowing her mom was an artist helped Hill understand why she had felt like a misfit, but the two didn’t become close. “I kept the relationship at bay,” she says. “They were just getting to know one another better,” adds McGraw, when White died in 2007. (Hill’s father died first, in a car accident.)

When Hill and McGraw began dating, they spent hours talking about how their relationship would never work. Marriages between artists, she notes dryly, “don’t have a good track record.” Nonetheless, they started a family right away.

In the late ’90s, Hill, with her torchy, grown-up voice, had the more successful career: “This Kiss,” “Breathe” and “The Way You Love Me” topped Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart and crossed over to the pop charts. “While she was doing press, I hung out with the kids. I was just ‘Mr. Hill,’” recalls McGraw.

Around 2001, Hill’s crossover success faded, and her chart results regressed to the mean. McGraw, however, was in the midst of a winning streak: He placed 23 consecutive singles in the top 10 of the Hot Country Songs chart, including five No. 1s in a row. So McGraw went on tour, and Hill stayed home with the girls.

Hill: He’s a legit touring machine. Had the tables been turned…

McGraw: I would’ve stayed home.

Hill: That was the best choice for our family. I don’t regret it at all.

McGraw: That’s the only reason she married me, so she could have kids and stay home.

Hill: Wow. Did you really just say that? Are you kidding me?

McGraw: I’m kidding!

Hill: I don’t mean I sat home on my butt and ate bonbons.

McGraw doesn’t have a classic country voice — “There are people working at 7-Eleven who can sing circles around me,” he likes to say — but he’s unmatched at picking highly emotional songs that also tell the story of his own maturation. Many of his early tracks were borderline novelties (“What Room Was the Holiday Inn,” “Refried Dreams”) until the 1995 hit “I Like It, I Love It,” about a guy who loses interest in his rowdy male friends and becomes happily domesticated.

Since then, while the country has been dominated by songs about endless summer nights, McGraw has distinguished himself by picking the kind of tunes that soundtrack milestones in people’s lives: weddings, graduations, funerals. Two of his biggest smashes, “Live Like You Were Dying” and “Humble and Kind,” are about hard-earned wisdom. Earlier in 2017, he and Hill released “Speak to a Girl,” a remarkable ballad in which they instruct men to respect women and tell women to demand that respect. At a time when toxic masculinity stretches from the country charts to the White House, McGraw has challenged Nashville’s restrictive gender roles. Along the way, he has lost a few fans: “When did Tim become such a pansy?” one wrote earlier this year on a country music website.

Country stars, on average, are more liberal than their fans, and most keep their political opinions to themselves to avoid alienating anyone. Speaking less than two weeks after a man with an arsenal of legally purchased military-grade guns shot and killed 58 people at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas (but before the Sutherland Springs, Texas, church shooting that killed 26), McGraw and Hill both make it clear: They support gun control.

“Look, I’m a bird hunter — I love to wing-shoot,” says McGraw. “However, there is some common sense that’s necessary when it comes to gun control. They want to make it about the Second Amendment every time it’s brought up. It’s not about the Second Amendment.”

Hill adds, “In reference to the tragedy in Las Vegas, we knew a lot of people there. The doctors that [treated] the wounded, they saw wounds like you’d see in war. That’s not right. Military weapons should not be in the hands of civilians. It’s everyone’s responsibility, including the government and the National Rifle Association, to tell the truth. We all want a safe country.”

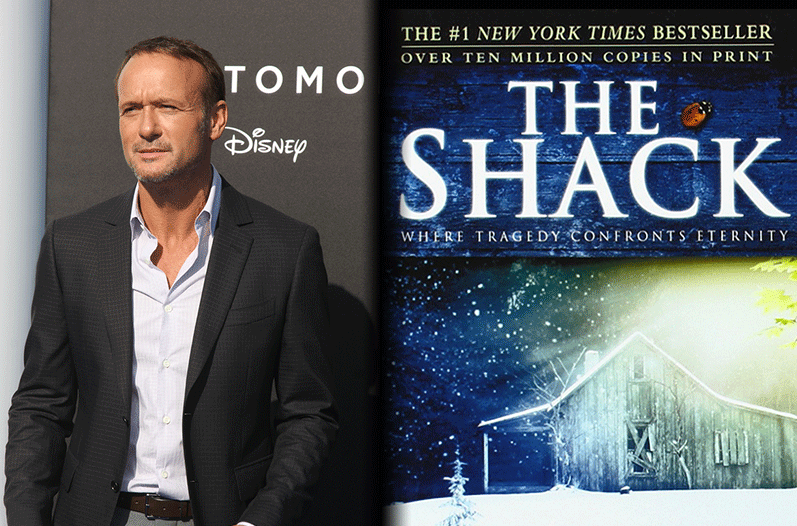

In 2008, McGraw — who has a nice sideline in acting, including The Blind Side and the Friday Night Lights movie — had a role in Four Christmases as Vince Vaughn’s doltish brother. When McGraw saw the film’s trailer with his daughters, they gasped at how bloated he had become and told him to lose weight.