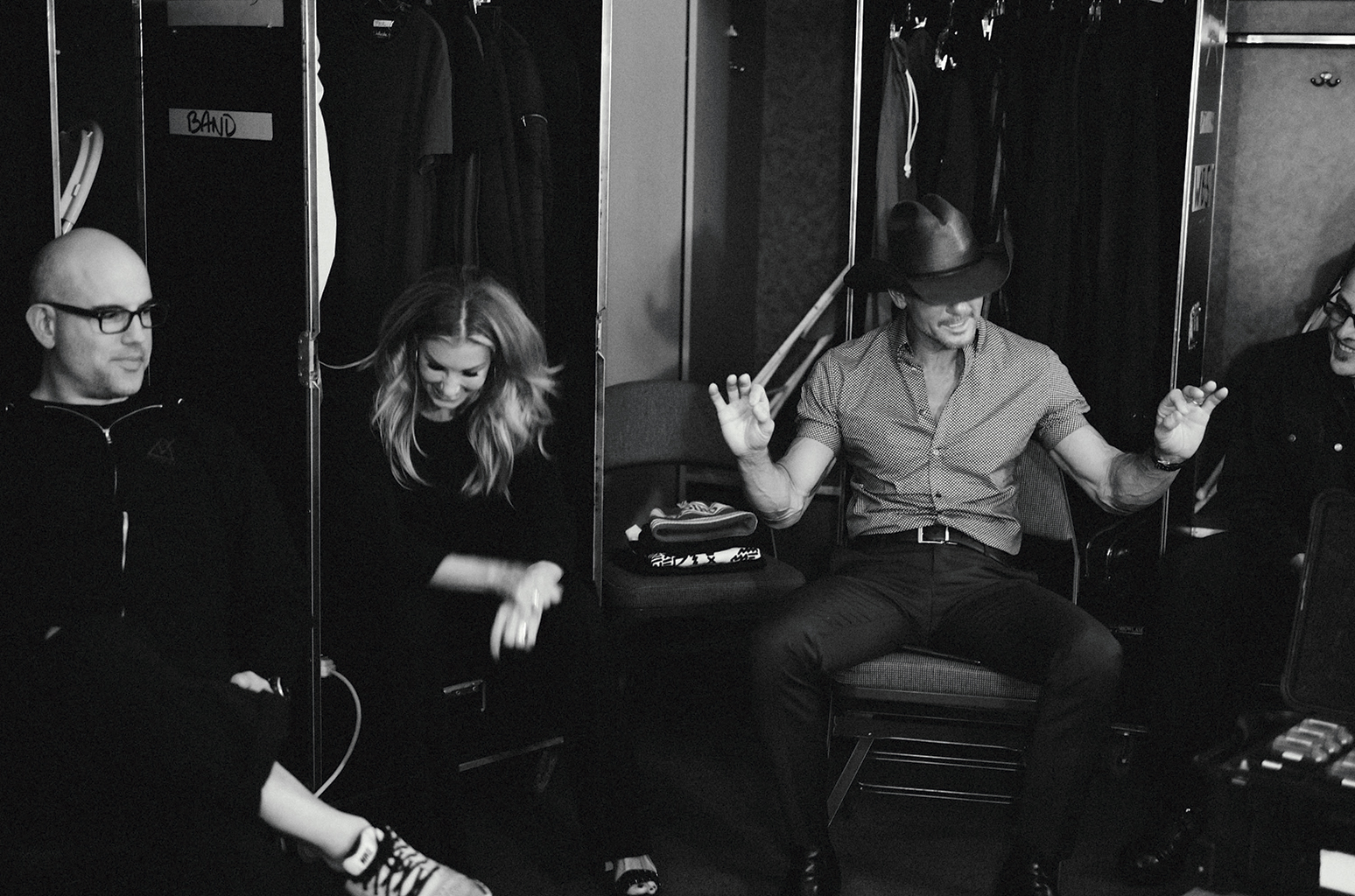

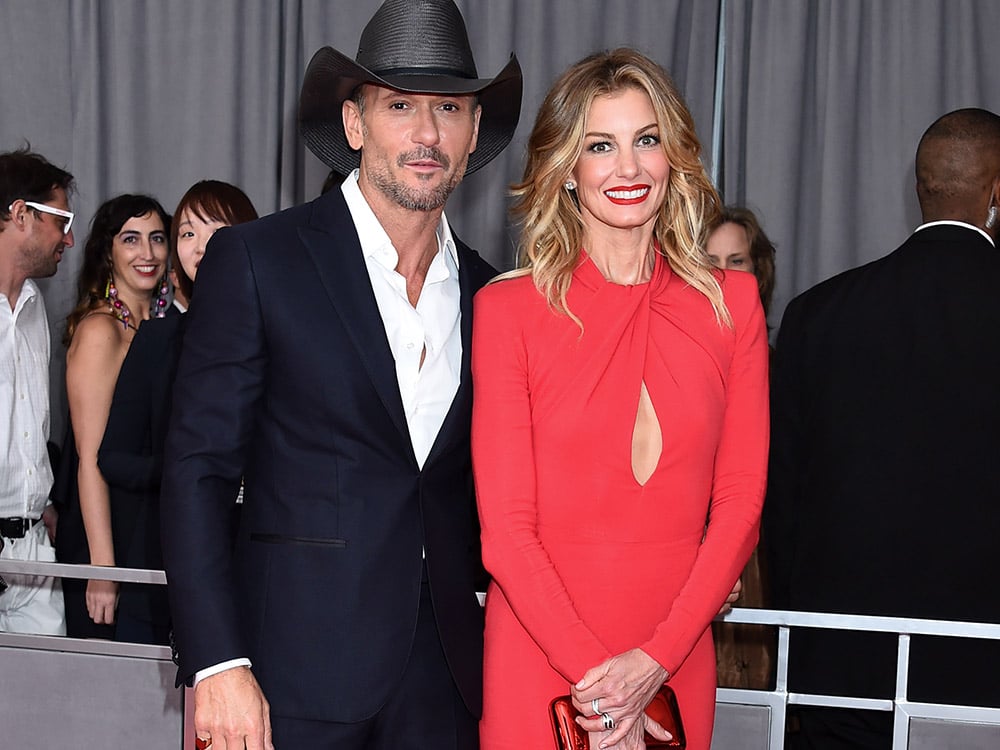

Faith Hill and Tim McGraw are hosting a meet-and-greet before their Friday-night concert at the Capital One Arena in Washington, D.C. As is the custom for touring artists, they make jovial chitchat with fans, many of whom have bought VIP packages; then everyone poses for a photo, which likely ends up as part of the family’s Christmas letter.

Hill, who hasn’t toured in over 10 years, can be skittish with strangers, but when fans — mostly couples — enter the black-draped photo area, McGraw puts them at ease. “You look like trouble,” he chirps at one guy with a goatee, who hasn’t been trouble in a few decades. To a woman who’s much slimmer than her man, he says, “You could have done a whole lot better than him.” The photographer snaps a photo, and the husband exits, delighted — as does the wife, perhaps with a new idea in mind.

Toward the end of the 20-minute event, two parents urge their shy 9-year-old into the photo area. Hill squats down and exclaims, “Oh, you’re so cute!” McGraw kneels too, and the boy smiles anxiously. “You’re not that cute,” declares McGraw.

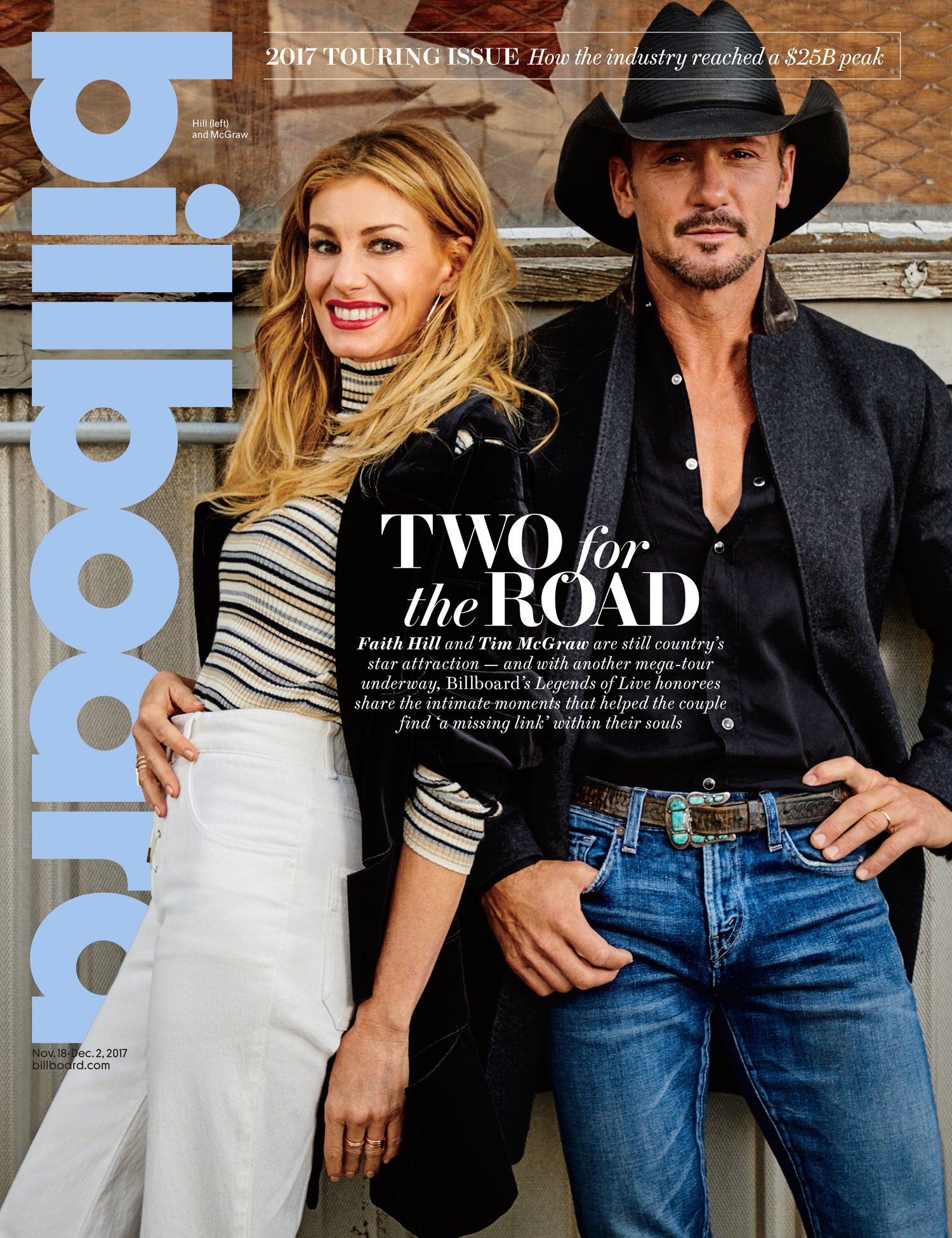

With a combined 100 years of life on earth and nearly as many hits, Hill and McGraw are as familiar as relatives to country fans, their images and reputations well defined: mischievous but sensitive Uncle Tim and gorgeous, sensible Aunt Faith, who put her music career aside to raise their three daughters.

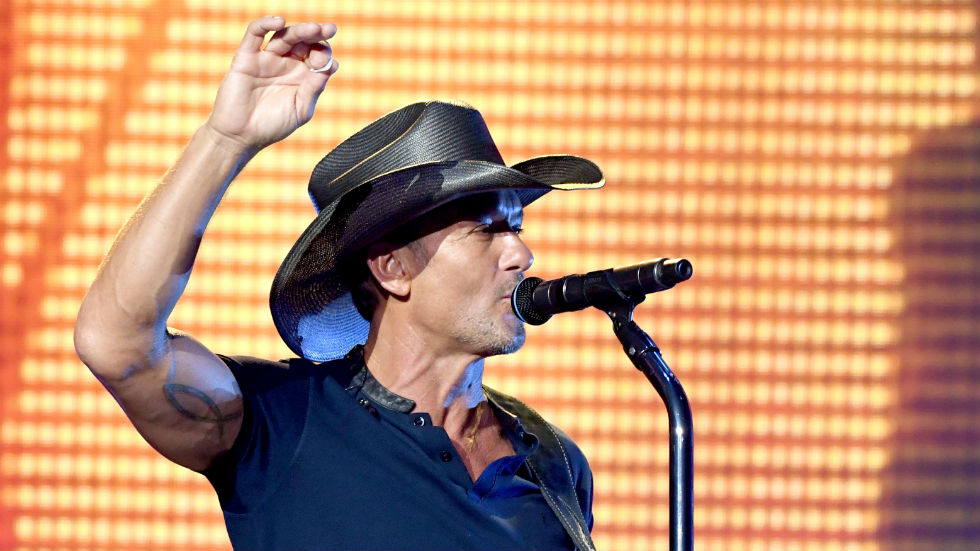

After 20 years of duets, they’ve released their first joint album, The Rest of Our Life, and launched the third iteration of their co-headlining Soul2Soul Tour, which continues well into 2018. Onstage, McGraw is deferential to Hill, if not worshipful. Offstage, he’s all that, but salty too.

View this post on Instagram

“I don’t see myself as a performer, just as a singer,” says Hill. “But I feel more relaxed onstage now than in the past. To be onstage with one of the greatest performers in our generation –”

McGraw interrupts. “Who’s going to be here?”

Hill: No, Tim is really a master at —

McGraw: Garth Brooks is coming tonight? Kenny Chesney?

Hill: Tim’s a master at his craft, and I wish he wasn’t sitting here to hear me say this because he can get a little cocky.

In his 20s, McGraw says, he found it easy to sleep on a tour bus, but not anymore. “This is another part of getting older because we’re both over 50 now, and…”

It’s Hill’s turn to interrupt: “We’re 50. Not over 50. Let’s make that real clear.”

“No, we’re past 50. Fifty’s gone,” insists McGraw.

He doesn’t sound sad about it.

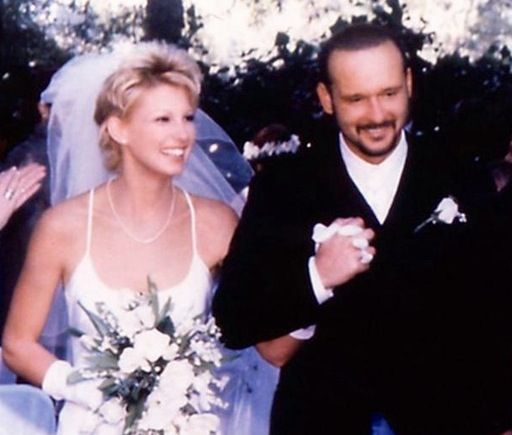

McGraw and Hill were on parallel tracks in their lives even before they knew each other. He released his first album in April 1993; hers followed six months later. When they met for the first time, backstage at a Country Radio Seminar showcase for new artists at the Opryland Hotel in Nashville on March 5, 1994, he was with a girlfriend, and she was separated from her first husband.

“For me, there was an intense physical attraction. I guess my girlfriend saw it in my eyes,” admits McGraw. “She said, ‘I don’t want you around her.’”

It’s just before 2 p.m. and we’re all in Hill’s dressing room, which is decorated in soothing shades of taupe and cream. Both are eating a late lunch: salad from the backstage buffet. “All right, let’s tear into this salad,” says McGraw, with more enthusiasm than lettuce deserves.

By 1996, Hill was engaged to her record producer, and McGraw was popular enough to start his first major headlining tour. Innocently or not, he picked Hill as his opening act. The tour started in March. By May, they were sharing a duet and a not-brief kiss onstage. In October, they married. For her next album, Hill hired a new producer.

Aside from their careers, what bonded the pair so quickly, says Hill, were the unusual details of their raising. “Although our stories are very different, there was a missing link within our souls that we both related to.”

“I had a very dysfunctional childhood,” says McGraw. “So I wanted what I didn’t have: a stable family.”

Until he was 11, McGraw thought a man named Horace Smith was his father. The two took long drives in his 18-wheel truck, hauling cottonseed, listening to 8-track cassettes of Merle Haggard and George Jones. “I remember sitting in countless truck stops, before the sun came up, listening to the jukebox. That was my education in country music.”

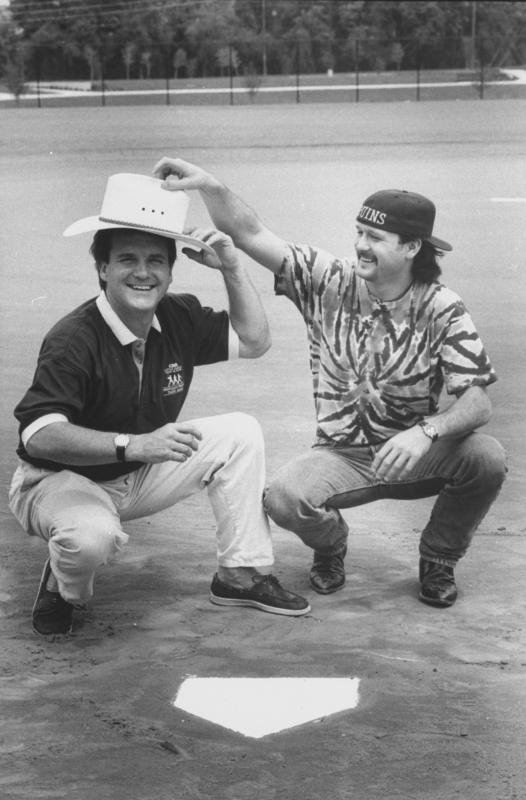

Then one day, he found his birth certificate in a drawer. Name of father: Samuel Timothy McGraw. Occupation of father: baseball player.

The summer before her senior year in high school, McGraw’s mother, Betty, had a fling with “Tug” McGraw, then an obscure minor-leaguer, and got pregnant. By the time Tim was born, Tug was a trail of dust. When she told him he had a son, Tug denied paternity — and withheld child support. She married Smith, who said he wanted to take care of her and had two kids with him. But Smith was a physically abusive drunk.

“My mom got the brunt of the abuse,” says McGraw. “I got abuse too because I wasn’t his. All he could see was somebody else’s kid — not to mention a baseball player’s kid, and here he is, a truck driver in Louisiana. He was envious.”

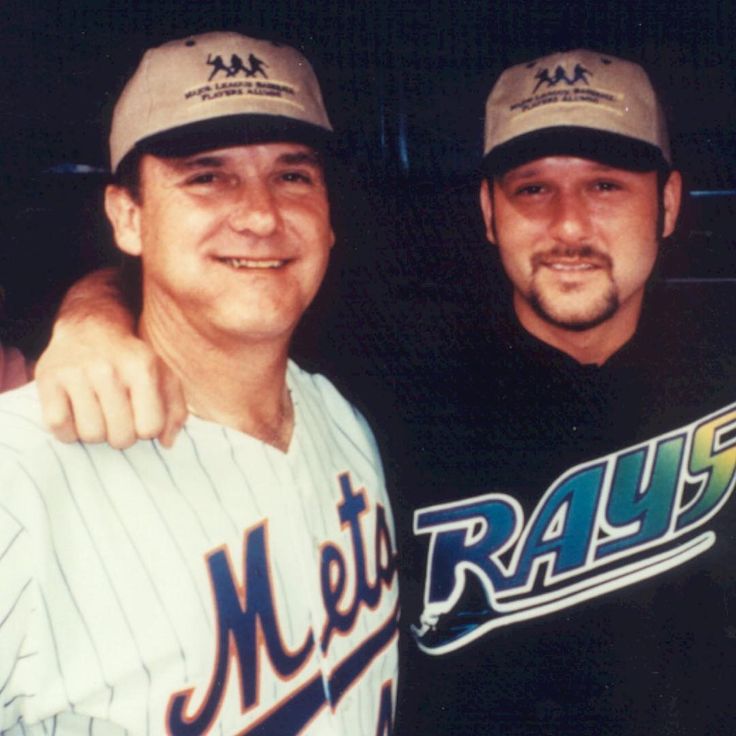

After Tim found his birth certificate, Betty contacted Tug again, and he agreed to meet them in Houston during the baseball season. The tug was friendly but aloof and didn’t stay in touch with Tim.

The following year, Tim and his mom drove to Houston again, but “he wouldn’t see us.” Tim was wearing a replica jersey with his dad’s name and number on it. “He was warming up in the bullpen. I kept yelling at him, but he wouldn’t look at me. I didn’t see him again until I was 18.

“I didn’t think it bothered me that much. But the older I get, the more I think about it.”

Later, the two grew close, and Tim and Hill cared for Tug after he was diagnosed with brain cancer. When he died, in 2004, Tug, who had gone on to pitch for 19 years in the National League and won a World Series with the Philadelphia Phillies, was living at the couple’s farm outside Nashville.

Tim still wondered why his dad had ignored him for so long but didn’t feel it was fair to interrogate a dying man. “I was hoping he’d bring it up. That’s one of my biggest regrets, that we never had that conversation.”