Simon went off to university to study economics and left his parents happily settled in Blackburn. He spent time in Spain, and in South Africa. It was during a trip back home in 2011, however, that he came to realize that all was not right with his Dad.

‘Mum had mentioned on the phone that he’d started to act a bit funny. He’d forget things. He’d get irritable. I brought him a book on Nelson Mandela. He asked me ten times if I’d bought it.’

Over the next few years, the situation deteriorated. ‘No-one mentioned the word Alzheimer’s. It actually took 18 months to get a diagnosis.

Mum would take him to the doctor and he’d go too and he’d say ‘I’m fine, nothing wrong with me’ and they’d go away again. There was an element of her not telling the whole story. She didn’t want to talk about how he was getting violent.

He was referred to a ‘memory clinic’ but we kept having to chase up the appointment. He was getting worse and worse.’

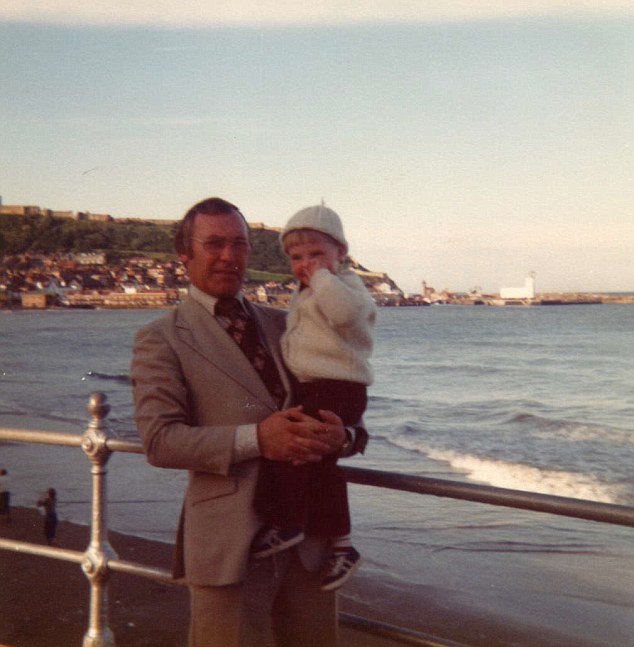

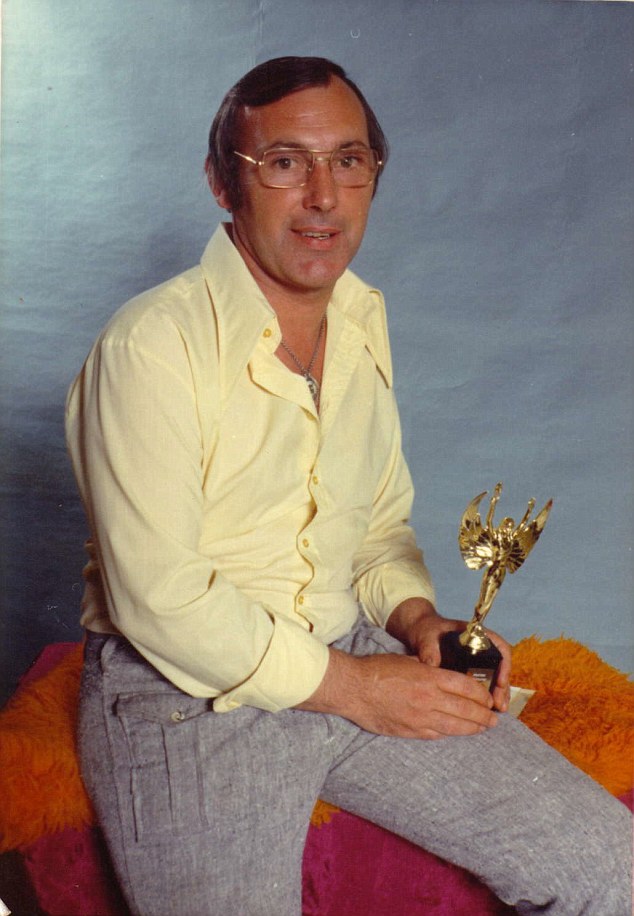

The big time never came calling, and when Simon was little, and the family had settled in Blackburn, his dad took a factory job and the singing became a part-time venture

Simon eventually witnessed the violent episodes himself and was devastated by them. ‘They used to go on holiday to France every year, to a caravan, and I went with them. It was hell. Dad would lose it.

‘He would pace up and down raging, shouting, calling me everything under the sun, calling mum everything. We couldn’t calm him down. I remember being properly scared.

All I ever remember him doing was singing. Ironically, he was known for his memory

‘Not long after I stayed with them in Blackburn and it was the worst time of my life. Dad just didn’t know who I was. One day I was out trying to get rid of moss from the paving slabs and he rushed out and was poking me like this (he stabs himself in the chest with his finger) saying “Who are you? What are you doing? Get out of my house, get out”.

‘When he got in a state like this, there was no reasoning with him, no calming him down. He’d veer between not knowing who I was and shouting “you are the worst son ever”. Mum was terrified.’

Getting the diagnosis gave a name to the condition, but as Simon desperately Googled the symptoms and prognosis, he was lost.

‘It’s the loneliest place in the world to be,’ he says. ‘And as it got harder I found it more difficult to cope. There was one particular weekend, last year, that I call World War Three. I was at home with them and Dad was awful, yelling and being aggressive.

What saved them, he says, was a call to the Alzheimer’s Society, the charity now benefiting from their astonishing story.

‘This was when I thought “he is going to kill us”. I remember just pulling the covers over my head in bed and crying my eyes out, then going on an internet forum about Alzheimer’s and tapping in “What the f*** do I do”.

‘That time we got the doctor and a social worker to come out. When I saw them coming up the drive I burst into tears. Friends were telling me that I couldn’t go on like this, I’d have to put him into care, but I couldn’t. He’d hate that. It would make him worse.’

What saved them, he says, was a call to the Alzheimer’s Society, the charity now benefiting from their astonishing story. ‘On that first phone call, I made no sense. I just sobbed. But they are used to that. They picked me off the ground and made me realize I wasn’t alone. Other people have to cope with this too, and so many have it worse than we do.’

The YouTube posting was just an extension of this desire to ‘make sure that I was always going to have his voice’, but obviously, when their rendition went viral, Simon was flabbergasted

In all this madness, though, there were moments of calm, even happiness. One day Simon realized, with a jolt, that his father was ‘better’ if there was music playing, or if he was singing. On bad days, he’d take him out for a drive, and get him to sing along to his own old backing tracks.

‘It was partly about getting him to do something he enjoyed, but it was for me too. I remember once coming down the stairs and hearing him sing Mac the Knife, his signature tune – but he’d forgotten the words. That was a real jolt for me, a sign that time was actually running out.’

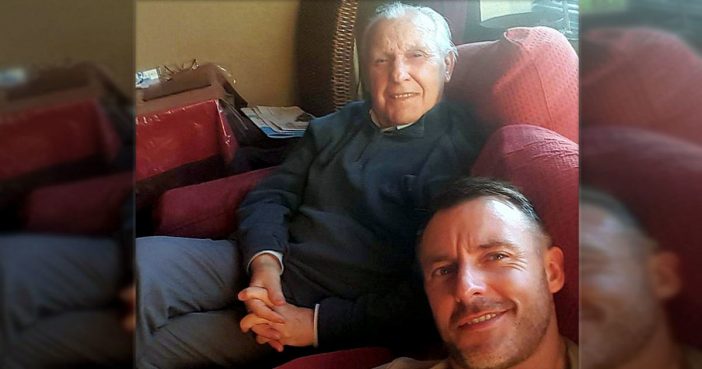

Their time together, singing in the car became therapy for them both. ‘We got to reconnect,’ admits Simon. ‘We’d chat away. By this stage, he wouldn’t know me, but he’d chat away about his son Simon who lived in London. He’d describe my flat to me.

‘He’d tell me he was proud of his son. I’d go along with it, pretending to be this other Simon.’ He fills up. ‘It is so hard. My dad never told me he was proud of me, he wouldn’t have, he wasn’t like that. But he could tell this other Simon.’

Knowing that they were on borrowed time, the idea of recording his Dad’s singing became more urgent. At one point he hired a recording studio himself, paying £130 to make his own record.

One day Simon realized, with a jolt, that his father was ‘better’ if there was music playing, or if he was singing. On bad days, he’d take him out for a drive, and get him to sing along to his own old backing tracks

‘It was a nightmare. The first two studios I called, explaining that I wanted to bring in my dad who had Alzheimer’s, said no. They thought I was mad. But the third one said yes.

‘When we got there, though, Dad wasn’t co-operative. He’d never recorded with headphones on and didn’t see why he needed them. He had a tantrum and said ‘who is this lanky t***?’ of the engineer. But I convinced him to give us one last try – and it worked. He sang his heart out, and the guy’s jaw dropped.’

All he ever wanted to do was to sing for people, and now people are listening to him all over the world.

The YouTube posting was just an extension of this desire to ‘make sure that I was always going to have his voice’, but obviously, when their rendition went viral, Simon was flabbergasted.

He admits that the offer from Decca to turn his dad into a bona fide recording star was a difficult one to process, though.

‘There was a part of me thinking ‘is this right?’ because it’s true, he doesn’t really understand what is happening. I had to discuss it with my mum, and we both sat there asking ourselves ‘what would Dad want?’.’ The answer was unequivocal. ‘There is nothing he would have wanted more in the world’.

There will be no happy ending here, not even if he reaches Number One, or an album beckons. The prognosis is never good with Alzheimer’s and Simon makes a downward slope with his arm when I ask what he thinks the future holds. At the same time, though, his father’s voice will now never die.

‘All he ever wanted to do was to sing for people, and now people are listening to him all over the world,’ says Simon. ‘He would love that. I know he would.’

Credits: dailymail.co.uk