Ingvar Kamprad, the man who created IKEA, leaves behind a professional legacy that’s all about simplicity: sleek, affordable, Scandinavian-designed furniture with wordless assembly instructions.

His personal legacy, however, is more complicated: from a reputation for strict frugality to flirtations with fascism.

But we’ll get to that.

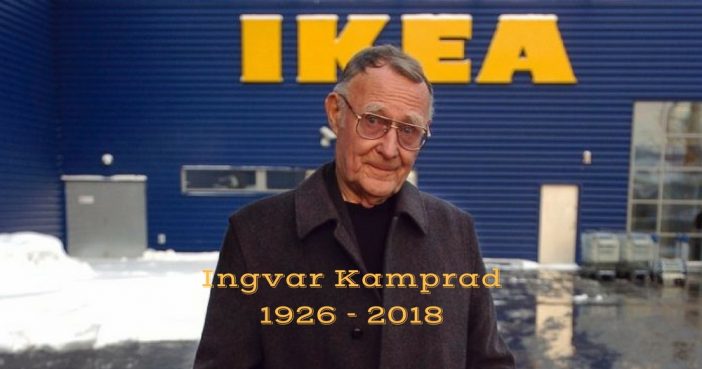

Kamprad died Saturday at the age of 91 at his home in Smaland in southern Sweden, with his loved ones by his side, according to a statement from IKEA. The company says he had faced a “short illness.”

“His legacy will be admired for many years to come and his vision – to create a better everyday life for the many people – will continue to guide and inspire us,” says Jesper Brodin, the CEO, and president of the IKEA Group.

The company Kamprad founded at 17 grew into a multinational behemoth, with nearly 400 stores worldwide, almost a billion store visits per year and more than $36 billion in annual retail sales in Europe alone.

Though the company — which never went public — was and remains secretive about its finances, it did reveal its balance sheet for the 2009 fiscal year. NPR’s Jacob Goldstein reported the upshot of the financial disclosure in 2010:

“The company is sitting on a huge pile of cash, and managed to grow throughout the economic turbulence of the past few years.

“In its 2009 fiscal year, Ikea made $3.5 billion in profits on $30.2 billion in revenues. And the company was holding $19.7 billlion in cash at the end of that year. (Ikea reported results in euros; I converted the figures to dollars at the current exchange rate.)”

The retailer hopes to generate $62 billion in annual revenues by 2020, according to Reuters.

Kamprad was born March 30, 1926, and — despite struggles with dyslexia — exhibited an entrepreneurial spirit from a young age, selling matchboxes as a small child. He quickly realized he could buy them dirt cheap in bulk and then sell them for a low price while still earning a profit. He later moved on to selling fish, Christmas decorations, and pens. He ran advertisements in local papers and also distributed a “makeshift mail-order catalog,” as the Associated Press reports.

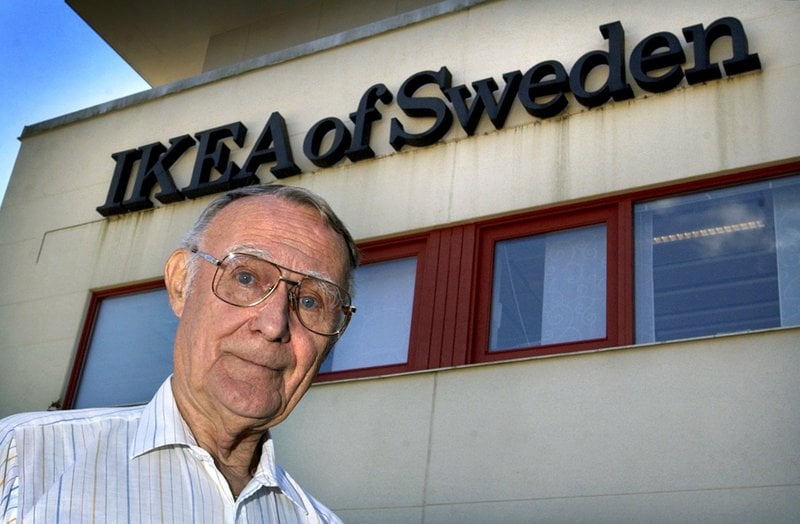

At the age of 17, he formed IKEA, an acronym built from his own initials and those of his family farm (Elmtaryd) and the local parish (Agunnaryd).

In 1950, he added furniture sourced from local manufacturers to his catalogs and, when it became evident that it was his most popular product, it became his sole focus.

Kamprad’s lightbulb moment arrived in the 1950s when he saw an employee removing the legs from a table to help customers transport it. He pioneered flat-pack furniture that would fit snugly inside its box, saving space and money. What’s more, the costs of assembly would be eliminated by letting consumers build their own furniture.

(What’s even more, research would later document an “IKEA effect” whereby customers derived more satisfaction from products they built themselves.)

Kamprad prioritized an image of austerity for himself and his company, even though Bloomberg Billionaires Index calculated his wealth at $58.7 billion and ranked him the eighth wealthiest man in the world. In a book he wrote about IKEA’s history, he wrote that he often perused local vegetable markets just before they rolled up shop for the night, always on the hunt for a better deal. He reportedly drove a modest Volvo, flew economy class (and made his executives do the same), ate cheap meals and stayed in budget hotels. He spent many years living in Switzerland to avoid Sweden’s steep taxes, a decision that rankled some in his home country.

Thrift was one of the virtues he laid out in a manifesto he published in the 1970’s titled, “The Testament of a Furniture Dealer.”

Reporters later found that his reputation for penny-pinching was not entirely accurate, however, as the New York Times reports:

“His home was a villa overlooking Lake Geneva, and he had an estate in Sweden and vineyards in Provence. He drove a Porsche as well as the Volvo. His cut-rate flights, hotels and meals were taken in part as an exemplar to his executives, who were expected to follow suit, to regard employment by Ikea as a life’s commitment — and to write on both sides of a piece of paper.”

In 1994, journalists uncovered another secret of Kamprad’s life — the one that would forever tarnish his legacy. The Swedish paper Expressen found letters showing Kamprad had corresponded with Per Engdahl, a prominent Swedish fascist in the 1940s and 1950s, enthusiastic about his ideology.

In a letter to IKEA employees in 1994, Kamprad called the relationship with Engdahl “a part of my life I bitterly regret.” He later wrote that his “delusions” about fascism were ingrained by his German grandmother who had been a strong supporter of Hitler.

Kamprad also wrote openly about his struggles with alcoholism over his lifetime.

IKEA’s statement Sunday says Kamprad “worked until the very end of his life,” although he had not occupied an operational role in the company since 1988. He acted as a “senior advisor” in the intervening years.

Kamprad is survived by his daughter and three sons.

(Source: NPR)