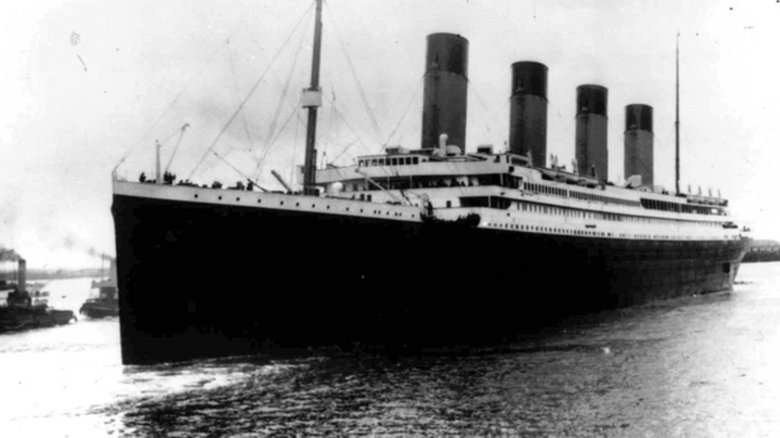

Predicting the Titanic

An “unsinkable” ship, described as “the largest craft afloat and the greatest of the works of men.” A recovering alcoholic for a captain, a collision with an iceberg, and a catastrophic loss of life. We’re not talking about the sinking of the Titanic—we’re talking about the sinking of the Titan, and it happened in an 1898 novella by Morgan Robertson called Futility. There were so many similarities that Roberston had to insist he wasn’t a clairvoyant, and while that’s certainly creepy, we’re not done yet.

The Titanic sank in 1912, and it made headlines across the globe. At the same time, Titanic was setting sail on its ill-fated journey, Popular Mechanics published a short story by Thornton Jenkins Hains (writing as Mayn Clew Garnett). The tale was about an 800-foot luxury liner that collided with an iceberg while steaming across the Northern Atlantic at a speed of 22.5 knots. Casualties are steep because there aren’t enough lifeboats. News of Titanic—an 882-foot liner that collided with its iceberg at 22.5 knots—appeared alongside the fictional tale.

And we’re still not done. Twenty-six years before Titanic sank, British journalist WT Stead published fictional The Sinking of a Modern Liner. That ship was sailing from Liverpool to New York City when it sank, and again, casualties were high because of an insufficient number of lifeboats.

WT Stead was onboard Titanic and died in the icy waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

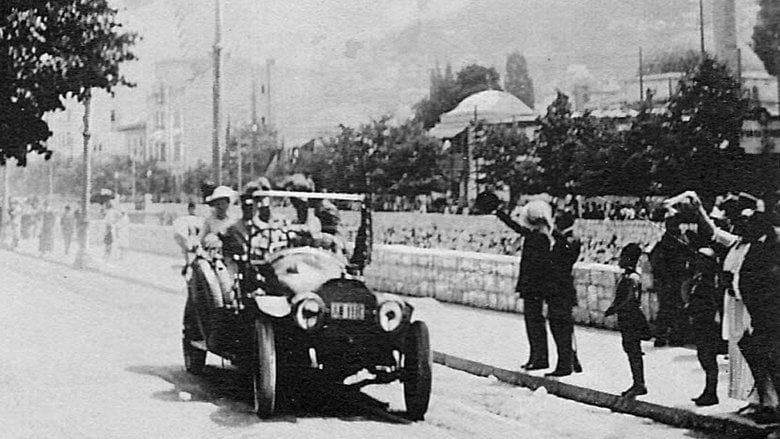

The license plate of the car that started World War I

In case you slept through this day in history class, a quick recap: One of the major events that kicked off the start of World War I was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. It’s one of those events that’s become so mythic that a ton of rumors have grown up around it, like the idea that in 1913 he killed a white stag and was targeted by a legendary curse that said his own life was forfeit. We’re not sure about that, but given that he kept records of his hunting kills and had ended the lives of 272,439 animals, Mother Nature might have wanted to have a little sit-down with him.

One of the strange coincidences that’s absolutely true, though, is about his car. It was a Graf and Stift double phaeton, and while it wasn’t the cursed car of death it was rumored to be, it did bear an odd message. The car ended up in the impossible-to-pronounce Heeregeschichtliches Museum of Vienna, where it sat for almost two decades before a British tourist pointed out the odd sign of the license plate. The plate—that hasn’t been replaced and can be seen in photographs of the assassination—reads A 111 118 … as in “Armistice, November 11, (19)18,” the famous date of the agreement that ended World War I.

Violet Jessop survived three White Star tragedies at sea

In the early 20th century, luxury liners were the bee’s knees. The White Star Line was one of the premiere ship-builders, and three of their biggest and best were the Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic. You know most of the story, but strangely, one woman was onboard every single one of them.

Her name was Violet Jessup, and she was an Irish nurse from Argentina. It started in 1911 when she was onboard the Olympic when it collided with the HMS Hawke. The Olympic didn’t sink, but Jessop’s friends convinced her that an even more incredible time was to be had working on Titanic … so she that’s where she headed next, and she was one of the survivors pulled from the freezing Atlantic by the Carpathia.

Not to be deterred by something clearly trying to send her a message, she went back to sea to serve on White Star’s Britannic, which was drafted into service as a hospital ship during World War I. That ship hit a mine, and Jessop found her way into the lifeboats yet again. This time, though, that lifeboat was dragged back toward the sinking ship and its propellers. Seeing other ill-fated lifeboats—and their passengers—chopped to bits by the propellers, she jumped, hitting her head hard enough that she would have headaches for the rest of her life.

You’re guessing she swore off ships forever, right? You’d be wrong. She worked as a ship’s stewardess until 1950.

America’s Civil War started and ended with Wilmer McLean

Saying you were there for the first shot and the last shot of a war that ripped a country apart sounds like the kind of one-upmanship that only happens after the drinks have been flowing for a while, but in the case of Wilmer McLean, it’s a totally legit claim.

In July 1861, McLean turned used of his Virginia home over to General PGT Beauregard, who was gearing up for the First Battle of Bull Run when a cannonball crashed through his kitchen. In his diary, the general wrote, “A comical effect of this artillery fight was the destruction of the dinner of myself and staff by a Federal shell that fell into the fire-place of my headquarters at the McLean House.” We’re tempted to suggest that McLean was less inclined to see the humor, but there you go.

Let’s fast-forward a bit and follow McLean as he moved his family farther from the front lines and to a cottage in Appomattox County, where he was certain he was well away from the fighting. Yet not only was he right in the middle of the final skirmishes of a dying war but when it came time for officials to choose a place for the end of the Civil War to be made official, they chose McLean’s parlor. That was all well and good, but they didn’t just sign documents, the men looted the house for souvenirs afterward. Talk about adding insult to injury.

An unfortunate advertisement seems to predict Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, changed the course of World War II, and it definitely changed the US role in it. Global tensions were, of course, high, and it’s terrifying to think that someone inside the country not only knew what was going to happen but was passing information out in the weirdest way possible.

The Pearl Harbor Visitors Center says that on November 22, 1941, the New Yorker ran a few ads for a dice game called The Deadly Double. Advertising is a product of the times, and these times dictated marketing the game with a major ad that showed the game being played by people hiding in an air raid shelter. Smaller ads also-ran, and it wasn’t until after the attack on Pearl Harbor that people started noticing what numbers were showing on the ads’ dice, including one ad with dice that showed 12 and 7. Other ads supposedly bore numbers that referred to things like the time and latitude of the attack, and if you’re thinking that military intelligence would be interested in something like this, they absolutely were… but it was an unfortunate coincidence.

The theory was so widespread that The New York Times even ran a piece on the game’s creator to debunk it, explaining that there was no actual link between the game and the war. The creator’s wife got in touch with the paper to say as much, and it was eventually chalked up to a bit of coincidence and a lot of people’s imaginations getting the better of them.