When it comes to Judy Garland’s private life, and the many challenges she faced, there is much to feel dismay over, but when the focus shifts to her career — whether it be live performances or starring in films like The Wizard of Oz, Meet Me in St. Louis or A Star is Born — it all feels golden. Yet from 1963 to 1964, Judy hosted her own television variety show that was so mired in turmoil, much of it caused by the CBS network, and conflict between her and CBS, that it was canceled after a single season. Ironically, today that show is genuinely revered as a classic and considered ahead of its time.

One of the world’s foremost experts on Judy Garland and The Wizard of Oz is historian and author John Fricke, who essentially traces the start of The Judy Garland Show to November 1959, when the actress-singer was close to death in a New York City hospital.

“At four-foot, eleven-inches, she had blown up to more than 180 pounds; the doctors did not expect her to live. She had been walking around for a couple of years without knowing she had hepatitis,” John explains, “and no matter how much she dieted, she didn’t lose weight, because the excess weight was fluid. Her liver was backed up after years of tonics, prescription medication and all the rest of it. Depending on which gossip monger you listen to, some insist it was cirrhosis, but when she died a decade later, the autopsy definitely concluded there was no trace of cirrhosis. In any case, they drained 20 quarts of fluid from her body and told her that she could never, under any circumstances, work again. She was 37 years old.”

Retirement Sounded Good

Upon hearing the news that she was forcibly retired, Judy reportedly threw her head back into her pillow, raised her hands and cried out, “Whoopie!!!” John details, “As she put it, she had been working for 30 years, full time, having started at two-and-a-half, and by the time she was seven she was in short films, radio shows, vaudeville and then with MGM at 13. She said she just wanted to get well and be with her children; they were all that really mattered to her, not singing, not being an entertainer, just taking care of her kids.

RELATED: Liza Minnelli and Lorna Luft Speak On Judy Garland’s Legacy Ahead of 100th Birthday

“Well,” he elaborates, “she made this kind of miraculous recovery. Across spring and early summer 1960, she’d recorded an album for Capitol, a song for the soundtrack of the movie Pepe, and had sung for the Democrats at their national convention, supporting JFK. In July, she went off to England to make more records. She was under contract at Capitol and they wanted to get stereo recordings of her greatest hits; they only had them in mono. She planned the trip as a vacation and they said, ‘Well, would you do this while you’re there?’ She said yes, because her voice was in great shape, she’d been resting, she was only allowed to drink a very mild white wine and she was healthier as an adult than she’d ever been.”

There was always the need for money — husbands notwithstanding, if Judy didn’t work, the family had no income — and Judy, on her own, decided that because she felt so strong and was singing great again, she would put together her first one-woman concert. This performer, who would supposedly never sing again, was starring in a two-and-a-half-hour, 30-song program, which she did at the Palladium in England, in Amsterdam, in Paris, and all across the UK from autumn to early winter of 1960.

“Since 1951 there’d always been ‘Judy Garland Live’ — at the Palace, at the Metropolitan Opera, all over the United States and in London — with the dancers and the costume changes and the chorus boys and all of that,” says John. “But this was so different. So pure. The programs for the show ultimately read, ‘Act One: Judy,’ ‘Act Two: More Judy.’ She just went out and did it. It was just a woman along with a 28, 35 or 40-piece orchestra singing 25 to 30 songs. A year earlier she was given up for dead, and now she was this astounding solo performer.”

This success brought her back to the United States, under the new management of theatrical agents Freddie Fields and David Begelman; the nefarious deeds of the latter, notes John, “caught up with him.” In a nutshell, Begelman spent years embezzling money from clients, including check forgery; he stole hundreds of thousands of dollars from Judy (which would be discovered later) and in the 1970s was caught embezzling from Columbia Pictures while serving as head of the studio.

Another aspect of Judy’s life at the time is that she had been married to Sidney Luft — described by Wikipedia as “an American show business figure” — since 1952, and between then and 1961, found herself about $300,000 in debt, largely due to Luft’s mismanagement of her money. But at that moment, she was still moving from success to success.

Relates John, “Freddie and David booked her nonstop in calendar year ’61. She did 40 of those one-woman concerts, including Carnegie Hall, the Hollywood Bowl and the Newport Jazz Festival. Plus, they placed her in Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg. The Carnegie Hall concert was in April and the two-LP set came out in July. By September it was on the top of the stereo and mono charts — it was the fastest-selling two-record album in history and eventually won five Grammys, including Best Female Vocal Performance and Album of the Year [the first time that honor was taken by a woman]. By the end of ’61, she recorded all the songs and the voice tracks for the animated film Gay Purr-ee. It was a prestige production with songs by Harold Arlen and “Yip” Harburg, who had done The Wizard of Oz, and animation by Chuck Jones. Then, the Carnegie Hall concert was in April and the two-LP set came out in July. By September it was on the top of the stereo and mono charts — it was the fastest-selling two-record album in history. Again, Judy Garland was literally back from the dead. So she finished 1961 with all of that under her belt.”

Television Beckons

In early 1962, Judy taped a CBS TV special with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, which was shown in February and became the highest-rated special program on CBS to that date. The day after that special aired, she was nominated for an Academy Award for her dramatic performance in Judgment at Nuremberg — news that greeted her as she was shooting Kramer’s A Child is Waiting, co-starring with Burt Lancaster in the film that dealt with developmentally-challenged children. And it just didn’t stop: That summer she went to England to shoot I Could Go On Singing with Dirk Bogarde.

Autumn 1962 brought her to Las Vegas for a six-week stint at the Sahara, one show a night. “Originally,” John says, “the deal was for three weeks, but she was doing such business that the management added a fourth and then broached an innovative idea, telling Judy, ‘We’ve got acts booked now for 8:00 and midnight for the next two weeks. Would you consider doing a show at 2:30 in the morning?’ She replied, ‘I’m always up then anyway, so why not?’ Bottom line is that she saw it as a way of getting out of debt.

“Now she and Sid had separated and reconciled and separated again during all of this,” he elaborates. “He was threatening to have her named an unfit mother and saying that she was hiding $2 million in earnings. Meanwhile, he had lived off of her for over a decade — and he didn’t love the fact that she had fallen in love with David Begelman, who was manipulating her, while robbing her blind as Liz Smith, the columnist, said years later.”

In November of 1962, Gay Purr-ee was ready to open and Judy appeared at the premiere in Chicago, while also agreeing to appear on Jack Paar’s television talk show, which aired every Friday on NBC. Enthuses John, “With two more movies in the wings and another TV special to do right after the first of the year in 1963, it’s no exaggeration to say she was the hottest act in show business, having become that over the preceding 18 months. She walked out on stage at the Paar show to a standing ovation from the studio audience, sat down and talked. Unless you saw Judy in person where she would tell anecdotes between songs — the general public didn’t know that she had this endless font of stories about vaudeville, about MGM, about her concerts, her friends — one or two of whom weren’t friends any longer after her candid stories were told! She looked great and sang three songs from Gay Purr-ee and the studio audience and TV critics were jubilant.”

So were the three networks, who, given her resurging popularity, by December 1962 had initiated an actual bidding war for Judy Garland’s services.

The Judy Garland Show

CBS ultimately won, striking a four-year arrangement that at the time was considered the single biggest talent deal in history: $24 million across four years if all options were picked up, out of which she would pay for the series’ production. Her company would produce and own the tapes outright; meanwhile, the network could not cancel the show after 13 weeks, and —whatever the ratings — they had to keep her if she wanted to stay.

John points out. “But there were two problems. In a 2003 interview with [CBS vide president of programming], Michael Dann pointed out that according to [CBS vice president of programming] Michael Dann: Fields and Begelman had made a good deal, but they knew nothing about placement. The Judy Garland Show was scheduled from 9 to 10 p.m., Sunday nights, opposite Bonanza, which was the established number one program in the country. Plus, it was in full color on NBC, while CBS was direly committed to black-and-white programming. There was some rationale behind this: Judy’s special with Sinatra and Martin had been shown in that time slot and blown Bonanza totally out of the water.

“Now if Fields and Begelman had been savvy,” he adds, “they wouldn’t have allowed that, not only because of the overwhelming challenge of it, but because it meant she was following the CBS Ed Sullivan Show. You don’t put two variety shows on back to back. But Fields and Begelman saw profit potential and sold her this bill of goods. You have to remember, the show’s budget every week was $150,000, so they were getting 15 to 20 percent of that off the top every week as her managers. They were also getting percentages of all the salaries of any of their own talent they could book on the show, be it guest stars, writers, producers, directors, and all of that. She could walk away with between $30,000 and $35,000 a week, but the show would rest on her shoulders. So that was just the back story — and with all of that going on, they started taping.”

https://twitter.com/judygarlandexp/status/948677386765299713?lang=en

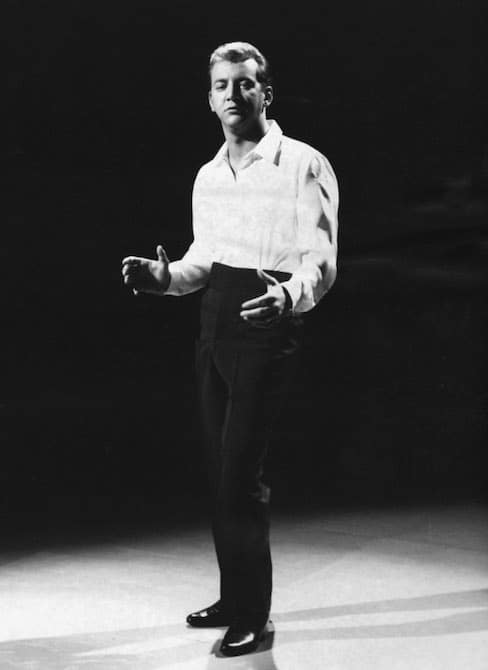

Episodes one through five were produced by George Schlatter (later the creator of Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In), who brought aboard Sing Along with Mitch’s Bill Hobin as director, Mort Lindsey as conductor of the show’s orchestra, Mel Torme as musical arranger and to write special musical material, and comedian Jerry Van Dyke as a series regular. Beyond comedy skits and musical performances from Judy and that week’s guests, the show featured two important segments: “Born in a Trunk,” during which Judy would share stories of her career and offer up a song; and “Tea for Two,” which featured her informally talking with a surprise guest. During the show, Jerry Van Dyke would appear in skits with Judy or the guests.

“After five shows, CBS fired George Schlatter,” John points out. “He conceived every show as ‘s special,’ a unique showcase for the very special Judy and her guests. CBS hated this; they wanted something predictable — not ‘special.’ Beyond that, without anybody’s knowledge, they had done test screenings of the show in America’s heartland, where people — apparently bred on The National Enquirer —regurgitated gossip: ‘Judy Garland? Oh, no, she drinks; she was mean to her mother’ and it went on and on. Beyond that, audiences were not then used to seeing unscripted, casual conversations in prime time. Variety shows were all very carefully scripted, and Judy’s was to a certain extent, but then they would say, ‘Okay, Judy will sit and talk to Terry Thomas,’ and that’s where the cue cards would end and she would just go on from there. When these shows started to be rerun in the 1980s, when TV had gotten to be so much looser, it was perceived differently. Ironically, two years after Judy’s series, Dean Martin came along with the most informal variety hour you could imagine and it worked.

“The other problem is that there were too many people watching TV on Sunday night expecting July Garland not to still be Dorothy, but certainly in her MGM all-American girl guise. The thing is, she was electrifying, she was terribly approachable, she was wonderfully sincere and you look at her on that show now and think, ‘God, how could America not love her in these shows when they listen to what she’s doing, when they look at her singing with the guests?’”

Take Two

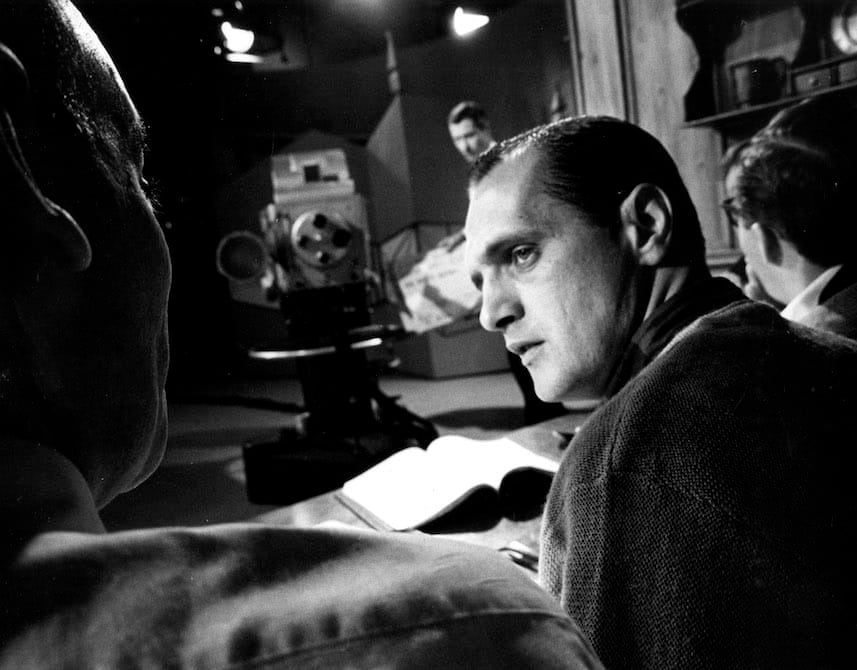

For episodes six to 13, CBS brought in producer/director Norman Jewison as Schlatter’s replacement, while firing Jerry Van Dyke following the 10th episode. New writers were brought in, whose idea of funny was to feed Judy self-deprecating lines to essentially diminish the legend a bit. While Jewison knew this was the wrong approach, his feeling was that this would make the show mainstream enough that it would get renewed for a second set of 13 weeks. She tried to be a team player, but it wasn’t easy.

“She starts to miss rehearsals out of her own insecurity,” says John. “It’s, like, ‘What am I going to face today? What are they giving me now?’ The real problem is that they weren’t giving her enough ‘Judy Garland Stuff’ to do. They were trying to make The Garry Moore Show or something so they could appeal to the Heartland. The episodes were aired out of order from when they were taped, and the first episode aired was Jewison’s second produced and it doubled Bonanza‘s ratings, but this was the new format where she was being referred to by Van Dyke as ‘a nice little old lady.’ Additionally, she wasn’t in good voice, the format changes had brought on laryngitis for a couple of episodes. The premiere was an okay show, but it was not what you’d expect from Judy Garland. Unfortunately, the damage was done. The second week, half the audience was gone; meanwhile, the announced guests on that second show were George Maharis, Jack Carter, The Dillards and Leo Durocher. For Judy Garland? That again is CBS saddling her with forced format and what they perceived ‘popular appeal’ performers.”

He adds to the story, “But to show you Judy’s instincts, two days before the episode that aired on October 6, 1963, she insisted on having 21-year-old Barbra Streisand as her guest. This was pre-Funny Girl on Broadway, but Barbra had made successful albums, was selling out nightclubs, and developing a TV following. Judy had seen her at the Cocoanut Grove that summer in L.A. and said, ‘Before she leaves town, I have got to have her on my show.’ CBS wasn’t keen on that idea, but Judy insisted. As I said, George Schlatter had introduced the Tea for Two segment, where Judy would sit and talk with her guests. This night she sat and talked with Barbra, and Judy complimented her: ‘One thing I love about you is that you really sing out and belt out a song. There are very few of us left!’ Of course, the audience applauded that and when they stopped, the camera switched to Ethel Merman, sitting in – and ‘singing out!’ — from the audience. This was planned, but the audience didn’t know and Barbra didn’t know. So Judy brought Ethel up on stage; the three of them talked about Funny Girl and – with Judy’s full encouragement and delight — Ethel kind of took over for four minutes.

“Judy was the biggest cheerleader in the world for her guest stars,” he says. “To wrap up this impromptu segment, all three of them sang ‘There’s No Business Like Show Business.’ This show was sensational; Judy’s duets with Barbra are among the greatest pop singing in TV history. CBS actually bumped the show with Maharis – and aired Judy and Barbra less than 48 hours after it had been taped. But the audience was back watching Bonanza.”

Take Three

As was the plan, Jewison departed after the 13th episode, replaced by Bill Colleran, who, emphasizes John, “had done countless variety shows and was a total Garland fan. He walked in, looked at the tapes and said, ‘What are they doing to her? This is the greatest singer in the world … why isn’t she singing?’ Colleran immediately did another revamp of the show’s format, removing insulting humor and putting the emphasis where it should have been to start with: on Judy and her singing. From his very first show, he brought in more guests who sang, he brought in writers with a sense of humor. They had a little bit of the deprecatory humor, but it was done very cleverly. Bob Newhart was the comedy guest and he had done his monologue when the show was about a half-hour in. Then, all of a sudden, you saw this middle-aged couple in bathrobes watching TV with their glasses on. And it was Judy and Bob Newhart making fun of themselves or, rather, what people had said about them. So it was good writing, but too little, too late – and none of it helped the ratings.

The real beginning of the end came with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, which hit Judy hard for personal reasons. She had not only campaigned for him, but they were actually friends.

“She would pick up the phone and call him – sometimes with business questions about financial aspects of the series,” John emphasizes. “She was always grateful, and in turn, he would gently say, ‘Now you do something for me’ and he would ask her to sing ‘Over the Rainbow’ over the phone. It was a very comfortable, non-sexual relationship, with JFK knowing how special she was and vice versa. So in the aftermath of his assassination, Judy called Colleran in — this was the beginning of their first work week — and said, ‘I want to scrap the show this week. I want to do the show, I just don’t want to do this show we’ve planned. I have a feeling that right now we need an affirmation of America and its values, so I want to do a one-woman concert of great songs like “America, the Beautiful” and “Keep the Home Fires Burning.” Not much talk if any. I’m not going to talk about Jack Kennedy, but we have to have a reaffirmation of faith in our country.’ Colleran flipped. He thought it could be one of the great hours in television history. But CBS said no.

“The feeling put forward — by CBS chief James Aubrey — was that by the time the show aired a month or so later, nobody would remember Kennedy,” Fricke incredulously explains and drily adds, “I think people still remember Kennedy in 2022, don’t they? But this is what Judy was up against. And she was livid. So she went ahead and did the scheduled show with Bobby Darin and Bob Newhart, and then did the Christmas show with her kids. But two weeks after CBS had said no, she said to the writers, ‘Forget about the finale this week. I have something special I’m going to do there. You don’t have to plan anything.’ She didn’t want it listed in the rundown, she didn’t want CBS to get any word of it. Thursday night was always the orchestra call and they’d go through all the music, but Judy did not sing her finale. However the chorus was doing their part and there’s no question: the song was ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic.’ And she did it at the taping the next day and got a standing ovation from the studio audience, the crew, everybody. Before she sang the song at dress rehearsal, she said quite simply, ‘This is for you, Jack.’ By then CBS had gotten word of it and said she couldn’t say that. But she went ahead and did the song – and the audience in the studio and the viewing audience at home got the message, regardless. And loved her for it.

“Although the rest of the season would still be produced, less than two weeks after that show was telecast, CBS canceled the series.”

There were, however, still seven shows left to tape despite the cancelation. So, Judy made the executive decision that for the first time since this whole thing had started, that it was going to be the show that she wanted it to be. And, having already signed The Judy Garland Show’s death warrant, CBS completely disengaged. As things went on, three of the episodes were one-woman concerts with the remaining shows having a musical guest.

“Judy and the guest would sing together,” explains John. “but she would do the majority of the show herself. Now all the way through the series, there were millions of viewers who watched, and many critics were aware of the high caliber of programming. And if the general public had remained unconvinced, they now seemed to figure out what she was trying to do.

“But even towards the end, things weren’t easy. The week before the taping of the 25th show, Sid Luft took her to court with headlines like, ‘Sid Luft accuses ex-wife of attempting suicide 20 times.’ Front page! She was beyond humiliated and embarrassed. She got to CBS on time for the orchestra call, but she said, ‘I can’t go down there and face these people after everything that’s been in the press. I haven’t slept the last 24 hours.’ Bill Colleran, this all-time gentle man and gentleman, helped her along, calmed her, soothed her and was her cheerleader. He genuinely loved her and said he knew it was a lot of effort, but it was absolutely worth it to go through with the episode.”

States John, “She kind of brightened up and said, ‘I’ve got an idea.’ She asked for the nurse to come up – Judy said, ‘Tell her to bring everything she’s got!’ — so that when Judy walked into the orchestra call half an hour later, she was completely bandaged up and on crutches. The headline ‘Judy Garland Attempts Suicide 20 Times’ was pasted across her chest, and on the back was a big sign that said, ‘Help!’ That’s how she got through the final rehearsal for episode 25.

“But the last show was too much for her. It was taped in stops and starts from Friday night until early Saturday morning, and even then they didn’t have enough for a full hour. So a week later she brought everybody back — she was hospitalized in between for suspected appendicitis, but insisted on checking out of the hospital and trying to finish the last show. She brought everybody back to CBS — the orchestra, the staff — on her dime and tried to tape the 20 minutes they needed, but just couldn’t get through it again. She tried to do the whole ‘Born in a Trunk’ routine from A Star is Born, but it was just too ambitious. If she had done five of her standards, she could have knocked it off, but she was trying to do a memorable final show. So the final show ended up with five numbers at the end that were lifted from earlier episodes. And that was The Judy Garland Show.”

Flashing forward to the late 1990s when Pioneer Home Video starts to put the series out on DVD from the original master tapes. All of a sudden, people who didn’t even know this show existed fell in love with The Judy Garland Show and fell in love again with Judy herself. Remarkably, the release of those 26 hours did a great deal to wash away the negative stories that surrounded so much of Judy’s life both while she was alive and after she’d passed on June 22, 1969, at age 47. As always, it proved that it all came down to the heart and soul of a genuine performer whose impact has transcended generations.

Closes John Fricke, “One of the critics from USA Today said, ‘This is the most important home video releases of the year, maybe of all time.’ You look at these shows and it’s proof positive that the failure of The Judy Garland Show had comparatively little to do with Judy. These are 26 great performances. Yes, she’s much better on some shows than she is on others, but none of them is a complete disaster. Even the three or four weak programs had the fail-safe finale: Judy on the runway, on the trunk, singing as only she could, and bringing it all home.”

For a look at the guests of all 26 episodes of The Judy Garland Show, please continue to scroll up.

Episode 1

Mickey Rooney appeared in episode 1, which was taped on June 24, 1963, and aired on December 8, 1963.

Episode 2

Performing in episode two is Count Basie. The show was taped on July 7, 1963, and aired on November 10, 1963.

Episode 3

The third episode featured Judy’s daughter, Liza Minnelli, as well as comedian Soupy Sales and musical act The Brothers Castro. It was taped on July 16, 1963, and aired on November 17, 1963.

Episode 4

Singer Lena Horne was featured as well as British comic actor Terry-Thomas. It was taped on July 23, 1963, and aired on October 13, 1963.

Episode 5

Tony Bennett is the musical guest with Dick Shawn taking up the comedy side of things. Taping took place on July 30, 1963, and it aired on December 15, 1963.

Episode 6

Judy was joined by singer Steve Lawrence and actress June Allyson for an episode that was taped on September 13, 1963, and aired on October 27, 1963.

Episode 7

Actor/dancer Donald O’Connor was a guest on this episode which was taped on September 20, 1963, and aired nine days later on the 29th.

Episode 8

Taping took place on September 27, 1953, with the show airing on October 20. Guests were Route 66 star George Maharis, comedian Jack Carter, bluegrass band The Dillards, and baseball player, manager, and coach Leo Durocher.

Episode 9

A truly great moment in TV history with Judy singing alongside Barbra Streisand and Ethel Merman. Taping occurred on October 4, 1963, and airing took place just two days later. Also appearing in the episode were the Smothers Brothers.

Episode 10

She did say she would miss him most of all, so it makes sense that Judy would reunite with the Scarecrow or, more precisely, Ray Bolger. Jane Powell also appeared in episode 10, which was taped on October 11, 1963, and aired on March 1, 1964.

Episode 11

Former Tonight Show host Steve Allen and actress Joyce Meadows joined Judy for the January 5, 1964 episode, which was taped on October 18, 1963.

Episode 12

Singer Vic Damone, actress, dancer and choreographer Zina Bethune and actor/singer/songwriter George Jessel were on the November 3, 1963, episode, which was taped two days earlier.

Episode 13

Singer Peggy Lee and comedians Jack Carter and Carl Reiner appeared on the December 1, 1963, episode, which was taped on November 8 of the same year.

Episode 14

Singer Bobby Darin and comedian Bob Newhart taped their episode on November 30, 1963, for airing on December 29th.

Episode 15

The Christmas Special episode aired on December 22, 1963, having been taped on the 6th. Judy was joined by kids Liza Minnelli, Lorna Luft and Joey Luft, as well as singer/actor Jack Jones and dancer/choreographer/teacher Tracy Everett.

Episode 16

Singer Ethel Merman returned to the show, joined by comedian Shelley Berman and dancer/choreographer Peter Gennaro. Taping on December 13, 1963, it was aired on January 12, 1964.

Episode 17

Actress/singer/dancer Chita Rivera was featured on the January 19, 1964 episode (taped December 20, 1963) along with the returning Vic Damone and comedian Louis Nye.

Episode 18

Judy reunited with her Easter Parade co-star Peter Lawford and appeared with singer Martha Raye and impersonator Rich Little on the January 26, 1964 episode, taped on January 14th.

Episode 19

French actor Louis Jordan and vocal ensemble the Kirby Stone Four were on the February 2, 1964, show. They all taped it on January 17th.

Episode 20

The first aired in the series of “Judy Garland in Concert,” this one subtitled the America the Beautiful Concert. She was joined by her kids Lorna and Joey Luft, airing on February 9, 1964 (an hour following The Beatles’ historic American debut on The Ed Sullivan Show) after being taped on January 24.

Episode 21

Singer/actress Diahann Carroll, still a few years away from her breakout role in the series Julia, appeared with Judy in the “Judy Garland in Concert” on February 16, 1964 show. It was taped on January 31.

Episode 22

Actor and singer Jack Jones returned to The Judy Garland Show on February 23, 1964, for the third concert episode. It was taped on February 14.

Episode 23

No guests this time, Just Judy in concert, performing “Music from the Movies.” Airdate: March 8, 1964, and taped on February 21.

Episode 24

Vic Damone was back for the third time, and in this concert episode, he and Judy performed a medley of songs from West Side Story. Airdate: March 15, 1964. Tape date: February 28.

Episode 25

In the series’ penultimate episode, Judy was accompanied by Jazz performer Bobby Cole. Airdate: March 22, 1964. Tape date: March 6, 1964.

Episode 26

It all ends here, with Judy by herself in concert, on March 29, 1964. The show was taped on March 13, 1964. An incredible series, despite so much interference, comes to a close.