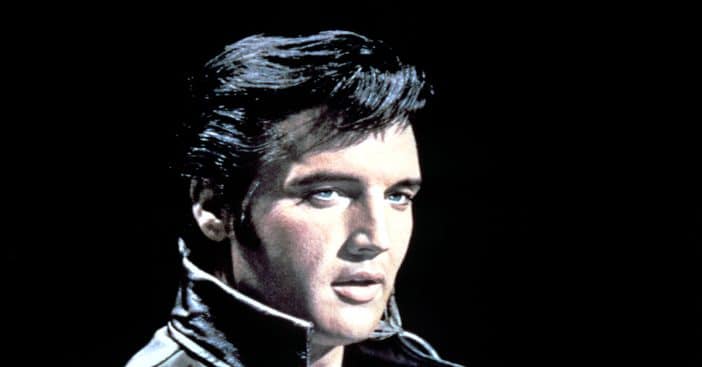

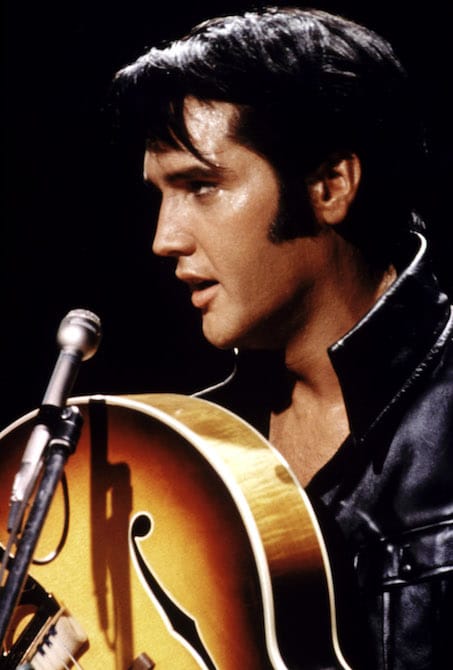

By the late 1960s, Elvis Presley’s career had taken a hit, some of which had to do with the arrival of The Beatles a few years earlier, which transformed the musical landscape. The other part of it was the reputation and legacy he was creating for himself by agreeing to make so many awful movies throughout the decade. But then came the opportunity for the 1968 television “comeback special,” which changed a lot of things.

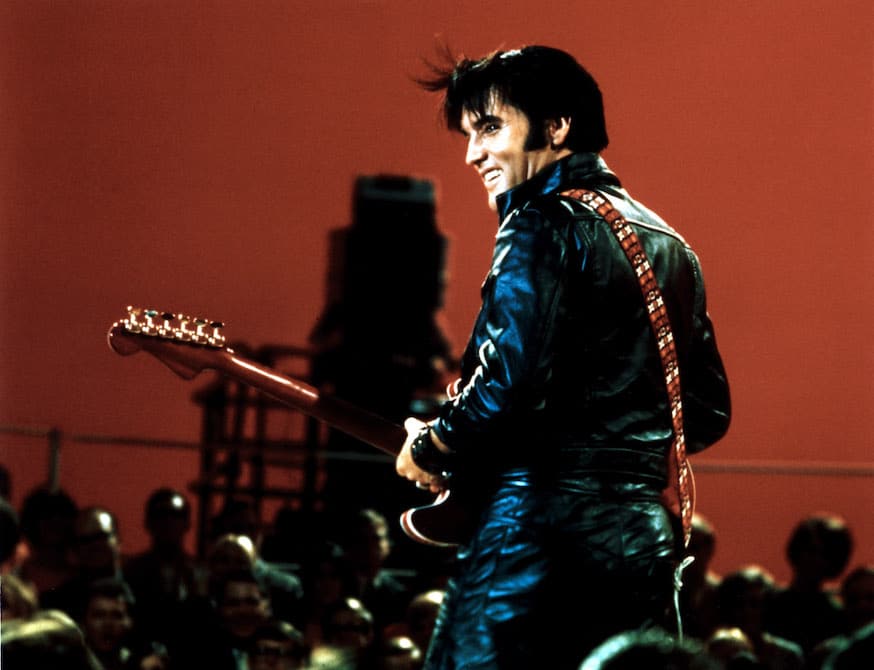

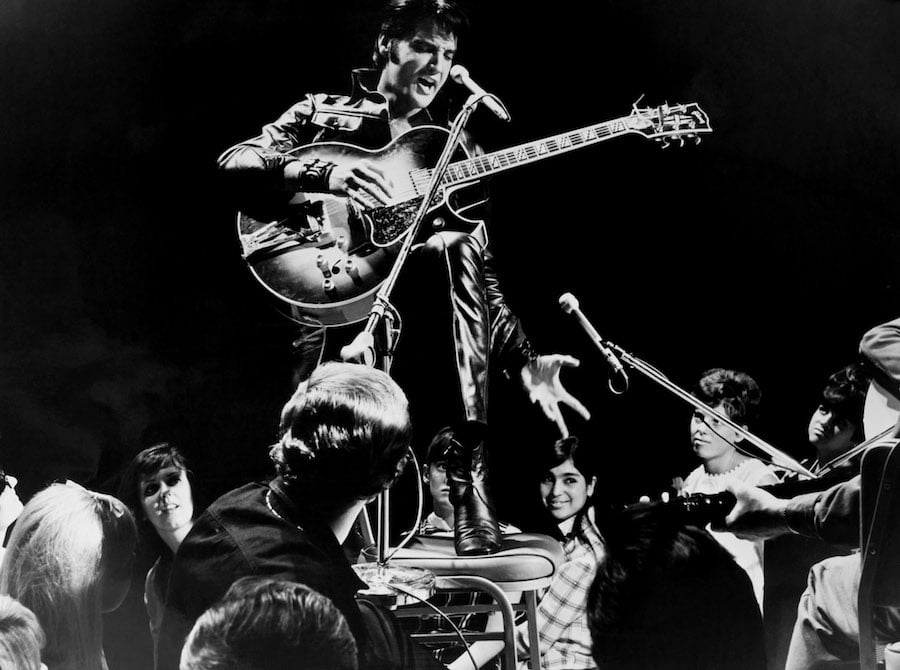

What audiences got to see was a rawer Elvis, and the King, in the part of the show that was an improv session, interacting with his fans, coming down into the crowd, and performing with them all around him. The mastermind of this was director Steve Binder, who had to not only push back against the desires of Elvis’ controlling and manipulative manager, Colonel Tom Parker, but convince Elvis to do the same.

Elvis’ Time to Rebel

Recalls Binder, who directed a large number of classic variety TV specials, “The Colonel tried to sabotage the improv session. Even to the point where he insisted that he would give out the tickets to the audience and when I showed up, there was no audience. We had to beg people, even at a drive-in restaurant eating breakfast, to come over and see Elvis Presley.”

“The Colonel was all about control and power, period,” he adds. “I had put no Christmas songs in the show and he refused to even let it be broadcast initially without one. Every day he would come in insisting that I put Christmas songs in the show. Elvis is the one who said, ‘I don’t care what the Colonel says, don’t put one in.’ And I didn’t. Then we got to the end where I delivered the master, and, thank God, in the improv, which was not scripted or rehearsed, he sang ‘Blue Christmas.’ But I saw major executives cower to the Colonel. It’s like the Colonel had some magical powers or something. I could care less; I could always go to work at my dad’s gas station.

RELATED: Elvis Presley Was ‘Ashamed’ Of Some Of His Movies

Elvis was a country boy for real, Binder suggests as reason that the singer seldom differed with Parker. He said, “I think he had a sense of gut loyalty because his father, Vernon, evidently had bonded with Parker, and I guess between the Colonel and Vernon they could get Elvis to do anything. You know, when we parted ways at the end, Elvis told me that after the experience he was never going to sing a song he didn’t believe in; he was never going to make a movie where he didn’t work with a great director. He went on and on and I said, ‘Elvis, I hear you, but I’m not sure you’re strong enough to stand up for yourself to do all that.’”

As Binder points out, his fears very much came true, Elvis dying on August 16, 1977, at the age of 42. The Colonel, he says, loved Vegas — in fact, in the end, he had gambled away his personal fortune — and Elvis in his last years spent much of his time booked there.

“I don’t think Elvis died of drugs,” he muses. “I think he died of boredom. After the special, I didn’t communicate a lot with him, because I was persona non grata insofar as the Colonel was concerned. I tried, but couldn’t get through to him and then I moved on. I mean, that just wasn’t my life. When I heard that he had passed away, I saw pictures of him as this bloated figure, but I just knew that he was trapped and he didn’t have the strength to get out of it. He ended up being a saloon singer in Las Vegas, which is the last thing he wanted to do. But, you know, every great story has some kind of great tragedy in it, and this is a great tragedy to me.”